songs

mahasiddha

iron chain bridge

architecture

sculpture

poetry

medicine

painting

philosophy

theater

Bhutan

Mongolia

Spiti

in general

Akademia Nauka, Warszawa, 1994

Hemispheres, No. 9, 1994, Warszawa Mandala, Mechernich, Sept. 1995, Nr. 2 in: Kalmus, Marek

Kalmus, Marek in: Odra, 7-8, 1989 in: Kuby, Clemens:Living Buddha, München, 1994 in: Anthropology of Tibet and the Himalaya, Zürich, 1993

in VDI nachrichten magazin 11/90

Tibets Leonardo

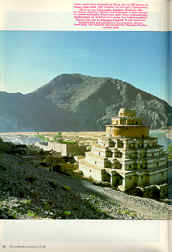

Einem asiatischen Leonardo da Vinci, der vor

500 Jahren im fernen Tibet lebte, sind Forscher auf der Spur: Thang-stong rGyalpo war

Universalist: Schmied, Architekt und Mediziner, Künstler, Dichter und Philosoph in einer

Person. Zu seinen wichtigsten Bauwerken zählt dieser siebenstöckige Stufentempel im

Westteil des Landes. Der Schutt zerstörter Dächer füllt die oft winzigen Kapellen in

den einzelnen Stockwerken und schützt ihre Innenwände, die mit wertvollen, erst

kürzlich dokumentierten Mandala-Fresken verziert sind.

Stellen wir uns vor: Eine Karawane von Yaks und

Tibetern zu Fuß erreichte eines Abends im letzten Licht des Tages Chuwori. Es war heute

später als üblich geworden. Sonst rastete man schon am frühen Nachmittag, bevor die

Winde das Kyichu-Tal erreichen, auf dessen Berghängen jetzt im Spätsommer schon oft

erster Schnee liegt, vom Sonnenuntergang gerötet, Nach Lhasa ist es noch eine Tagesreise.

Seit Monaten war die Karawane unterwegs; sie kam aus Bhutan, aus der Nachbarschaft der

späteren Klosterfestung Drukyel rDzong im Paro-chu Tal. Die Last der Yaks war

ungewöhnlich. Die alten Mönche des großen Klosters Chuwori hatten so etwas noch nie

gesehen. Den sehr jungen Novizen müssen ob der Sensation heimlich die Augen geglänzt

haben, wenn sie ihr Gesicht auch sicher mönchisch verhalten hinter einem Zipfel der

dunkelroten Robe versteckt hielten, weil ihr Tutor wohl nicht weit von ihnen stand.

In den ledernen Packtaschen der Yaks lagen

schwere geschmiedete Ketten und Eisenkettenglieder, länger als eine Handspanne, einen

Fuß lang etwa, dicker als ein Daumen und ohne den geringsten Rostansatz. Jeder wollte sie

anfassen und prüfen. Halbfertigfabrikate würden wir sagen, noch offene längliche

Rechtecke mit rund geschmiedeten Ecken, ähnlich einer ins Rechteck gezwängten Ellipse,

vorbereitet, um sie hier am Ort ineinanderzuhängen, zu schließen und zu Ketten von einer

Länge von fast 70 Metern zu verschweißen.

Der Herr Chuworis, ihr Abt Thangstong rGyal-po,

TG, der "König der weiten Ebenen (des Bewußtseins)", wie man ihn nannte, hatte

sie kommen lassen. Vor Jahr und Tag war er, wie so oft in seinem schon jetzt langen,

69jährigen Leben, unermüdlich und mit enormer unerklärlicher Energie ausgestattet, auf

Reisen gewesen, "bis ans Ende der tibetischen Welt", zwischen Kaschmir im Westen

und Assam im indischen Nordosten. Unterwegs hatte er gepredigt, initiiert, Gesänge

komponiert, geheilt und meditiert, neue Bildwelten entworfen, gezeichnet und gemalt, die

umherziehenden Barden gefördert und schon die Idee eines tibetischen Theaters im Kopf

entwickelt, hatte selbst geschmiedet, wie er es als Kind gelernt hatte, Skulpturen gehauen

und gießen lassen und herausgefunden, daß sich auch edle und halbedle Steine wie

Bergkristall als Material für Skulpturen eignen. Und er hatte entdeckt, vielleicht auch,

wie die Legende sagt, von den Musen, den Dakinis, eingeweiht, wie man Eisen rostfrei

schmiedet, besonders an den Nahtstellen, den Überlappungen, auf “ewige” Zeiten

- bis heute zum Beispiel, über 500 Jahre lang. Denn wir sprechen vom Jahr 1430.

Auch für die Nomaden unterwegs auf dem

Karawanenweg über 6000 Meter hohe Pässe von Phari in Bhutan

Glanzstück der Brückenbaukunst von

Thang-stong ist die im Jahre 1436 erbaute und von Wolf Kahlen 1988 entdeckte

Eisenkettenbrücke bei Cung Riwoche, welche in zwei Abschnitten die Ufer des Flusse

Brahmaputra miteinander verbindet. Blumengeschmückte Opferchörten am Steilufer zeigen,

daß sie den tibetischen Buddhisten heilig ist. Solange die Brücke existiert und verehrt

wird, glauben sie, wird auch ihre Religion Bestand haben.

durchs Chumbital nach Norden in die Provinz

U-tsang in Tibet, wie für Tausende Mönche, Pilger und Dorfbewohner in der Nähe der

heiligsten Stadt Tibets, waren diese rostfreien Metallstücke ein reines Wunder.

Eigentlich hatte sie niemand transportieren wollen. Seine Zeitgenossen hatten die Idee

für verrückt gehalten, das Eisen durch den Himalaya zu bewegen, aus dem Kongpo-Gebiet im

fernen Südosten Tibets oder aus Assam nach Bhutan, dort zu schmieden und es dann in

Hunderte von Kilometern weit auseinanderliegende Gebiete Tibets zu bringen; für möglich

allerdings wohl, denn sie kannten die Zähigkeit ihrer Tiere und Karawanenführer. Der

wundertätige Mahasiddha, der mit "großer Kraft" Ausgestattete, aber hatte sie

überzeugen können. Als die bhutanesischen Schmiede eines Tages meuterten und den

Vergleich zogen, es sei ebenso unmöglich mit der Last nach Lhasa zu gelangen wie die

schweren Ketten in den nächststehenden Baum zu hängen, nagelte er sie in ihrem

Versprechen fest: wenn er die Ketten in den Baum hänge, dann müßten sie für ihn die

Ketten die ersten Tagesreisen tragen. In der Nacht hängte TG alle Ketten in die Bäume.

Das erfüllte sie am nächsten Morgen mit Schrecken, der sich in Ehrfurcht verwandelte,

jetzt empfanden sie es als einen Segen, diesem Heiligen helfen zu dürfen. Außerdem wurde

ihnen nun erst klar, daß sie sich und anderen damit einen Pilgerweg von Bhutan und Sikkim

nach Lhasa eröffneten, wenn endlich ein gefahrloserer Weg über den Kyichu geschaffen und

der Umweg um Wochen verkürzt werden könnte.

Viele Tiere und Träger hatten sich abgelöst,

aus den grün bewaldeten abgeschlossenen Fürstentümern Bhutans bis hinauf nach Phari,

mit Hilfe des Fürsten von Gyaltse über endlose Pässe "hinunter" in die

trockenen Hochebenen, und in die sandverstaubten Flußtäler des Kernlandes des

tibetischen Buddhismus. Kurz vor dem Ziel war die Karawane bei Gongkar überfallen worden,

und die Bewohner der Gegend hatten 86 der 200 Eisenladungen für ihre Schwerter und

Geräte mißbraucht. Es gab zu dieser Zeit noch keinen wiedergeborenen obersten geistigen

Führer, die Dalai Lamas wurden erst viel später als solche erkannt.

Tsongkapa, der große Reformator, wachte über

die Geschicke im Jokhang, dem Heiligtum Lhasas, während die mächtigen Klosterstädte und

-universitäten in Drepung, Sera und Ganden erst in der Gründung und Entstehung waren.

Dies war die Zeit auch für eine verkehrsgeographische Renaissance, für eine neue

Infrastruktur, für Brücken, Fähren, Architekturen, Strukturelemente, die auch das

Zeitmaß der Tibeter wesentlich verändern sollten. Tsongkapa war der geistige Führer der

Zeit, TG ihr künstlerischer, sozialer und technologischer Pragmatiker, ein Universalist

in Lehre und Praxis, ein multimedialer und interdisziplinärer Arbeiter als Künstler

aller Künste, ein Leonardo Tibets. Sein Brückenschlagen war nicht nur eine symbolische

Idee, sondern auch ein organisatorischer und technologischer Triumph und eine

künstlerisch architektonische Tat. Die soziale Leistung, in allen Landesteilen des

ungeeinten Tibets Brücken zu bauen, ist einzigartig.

Als Schmied war TG, weil Schmiede der Erde

etwas entnehmen, einem der untersten "Stände" zugeordnet. Zugleich war er aber

Philosoph, an der Spitze der Verehrung, obwohl er sich immer wieder inkognito im Lande wie

ein Bettler bewegte. Auch dieses soziale Brückenschlagen hatte Methode. "Seine erste

Expedition auf der Suche nach Eisen wurde motiviert durch ein Ereignis an der Fähre über

den Kyichu vor Lhasa (dort wo später seine Brücke entstand). TG wollte den Fluß

überqueren, wurde aber wegen seines Aussehens (als Bettler) vom Fährmann zurückgewiesen

und nach einem Schlag auf den Kopf mit dem Ruder über Bord geworfen. Dies vermittelte ihm

die Einsicht in die Not der Armen und die Ungerechtigkeit ihnen gegenüber, und er

gelobte, an eben dieser Stelle eine Brücke zu bauen, "damit alle Menschen ohne

Diskriminierung den Fluß überqueren konnten", so schreibt der Tibetologe Stearns -

Mitglied in unserem Expeditionsteam - in seiner Analyse des Lebens von TG. Selbst die

heutige chinesische Regierung, die auf das tibetische Volk herabschaut, muß inzwischen

anerkennen, daß diese historische Persönlichkeit Tibets vielleicht als einzige - den

Beweis antreten kann, ein "guter", ein "fortschrittlich denkender” ein

"sozialer" und ein "wissenschaftlich-technologisch interessierter"

Tibeter gewesen zu sein. Darum ist die Chinesische Akademie der Sozialwissenschaften an

unserer Forschung - der Erstellung eines umfassenden Portraits dieses tibetischen

Universalisten - sehr interessiert und möchte sich an ihr beteiligen.

Im Spätsommer 1988 führte ich die Erste

Internationale Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition zwei Monate durch Nordindien, Spiti, nach

Nepal und Tibet. Die Expedition, in den verschiedenen Ländern aus zum Teil wechselnden

Teilnehmern besetzt, bestand im Kern aus dem amerikanischen Tibetologen Cyrus Rembert

Stearns, dem polnischen Buddhismuswissenschaftler und Geologen Marek Kalmus, dem

polnischen Kameramann und Ritualforscher Waldemar Czechowski, dem Tibeter Padma Wangyal

und mir als Künstler, Filmemacher und Tibetforscher.

Schon 1985, als Consultant for Art and

Architecture der königlichen Regierung von Bhutan, hatte ich in Reliefs, Skulpturen und

Thangkas von der besonderen Verehrung TG's erfahren und war ihm zufällig und

Insgesamt 50 bis 60 Eisenkettenbrücken,

heißt es in alten Chroniken, ließ Thang-stong erbauen. Seine Schmiedetechnik war

geradezu revolutionär: Die jahrhundertealten schweren Eisenkettenglieder zeigen keinerlei

Rost, die arsenhaltigen Nähte sind übergangslos verschweißt. Geflochtene Lederriemen

und Seile halten die Holzbohlen der Brücke zusammen, farbige, im Wind flatternde

Gebetsfahnen sind an ihr befestigt.

wiederholt, auch unter merkwürdigen

Umständen, begegnet, Die Bhutanesen halten ihn eifersüchtig für einen der ihren, was

TG's größtem Wunsch der überregionalen Universalität sicher widerspricht. Für uns ist

er, wohl in seinem Sinne, eine über allen Lehrtraditionen des tibetischen Buddhismus

stehende Persönlichkeit, wie unterschiedlich sie auch in Bhutan, Spiti, Sikkim oder Tibet

Kagyupa, Ningmapa, Drukpa, Shangpa, Gelugpa oder Sakyapa heißen mögen.

Alle Brücken TG's in Bhutan waren bis auf

eine, von der wir erst später erfuhren - von Fluten, Erdrutschen oder durch

Vernachlässigung zerstört. Die Kettenglieder und -teile jedoch wurden wie Reliquien in

Klöstern, am Königshof oder bei Regierungsbeamten würdig aufbewahrt. Im Kloster

Tamcho-norbu-gang, dem Familiensitz direkter Nachfahren TG's hingen die schweren Objekte

der Verehrung auf Dachbalken aus, während am Fuße des Klosterberges eine neue kleine

Brücke an der Stelle der alten Brückenfundamente den Fluß überspannte. Eine geheime

Biographie TG's, die erst beim Eintauchen in Wasser sichtbar wird, war aus der

Klosterbibliothek verschwunden.

Alle befragten heutigen Äbte, Reisenden,

Tibet- und Bhutankenner winkten ab, wenn die Frage auf noch bestehende Brücken kam.

"In Tibet gibt es sicher keine mehr, wenn, dann nur in Bhutan", hieß es. Aber

da waren sie ebenfalls nicht mehr existent. Aus dem Studium diverser Biographien und der

Übersetzung einer zuverlässigen Quelle des 16. Jahrhunderts kannten wir ungefähre

Ortsnamen, besser gesagt nur Distriktsbezeichnungen, aber auch genaue Jahreszahlen und

viele Geschichten. Kein lebender Augenzeuge schien uns helfen zu können. Nur ein hoher

reinkarnierter Abt in Nepal erinnerte sich an eine Brücke, die er vor der

Kulturrevolution im Norden Lhasas überquert hatte. Die oben erwähnte Brücke über den

Kyichu im Süden stand noch in den ersten Jahrzehnten des Jahrhunderts, erinnerten sich

alte Lamas im Exil in Dharamsala genau. Ein Photo der Restketten einer Brücke sandte uns

Hugh Richardson, der in den 40er Jahren englischer Vertreter in Tibet war. Es konnte nur

Sehnsüchte wecken, sie aber nicht stillen. Aber wir wollten es genau wissen.

Ich hatte in Bhutan die Eisenketten in den

Händen gehabt, kannte also ihre Größe, ihr Gewicht, ihre Textur und Patina, wußte,

daß sie von TG's eigener Hand eingehämmerte Inzisionen haben könnten, vorzugsweise

einen Doppelvajra, einen doppelseitigen Donnerkeil, ein Diamantzepter. Aber in Bhutan

hatte ich keine Gravierung gefunden, auch keine intakte Brücke mehr, bis wir einen

Hinweis auf Ostbhutan und dazu einen photographischen Beweis von Harrer erhielten, Leider

konnte die Expedition 1988 nicht auch noch nach Bhutan fortgesetzt werden. Wir sollten

aber wesentlich mehr Glück haben.

Wir waren sehr gut gestimmt im August 1988, als

wir im für Ausländer verbotenen und auch für Inder schwer zugänglichen Spiti mit einer

Genehmigung arbeiten durften und eine sensationelle Entdeckung machten: Wir stießen auf

ein seit 60 Jahren verlorengeglaubtes, nicht vollständig dokumentiertes magisches

tibetisches Ritual, das TG zugeschrieben wird, das dazu noch mit animistischen

Bönrelikten durchsetzt ist. Mit diesem heute noch praktizierten Ritual soll TG eine

unheilbare Krankheit in Lhasa ausgerottet und die dämonischen Widerstände beim Bau

seiner ersten Brücke überwunden haben. In Lhasa, herbeigerufen von Tsongkapa, hatte er

den für die Epidemie verantwortlichen Dämon in einem Felsstein lokalisiert, in dem er

sich verkrochen hatte. Nun diente dieser Stein als Türschwelle zum Haupttempel Lhasas, TG

ließ den Stein auf den Marktplatz tragen, opferte, bat und drohte schließlich dem

Dämon, den symbolischen und wirklichen Stein und damit den Ort zu verlassen. Als jener

sich nicht beeindrucken ließ, auch nicht durch einen magischen Schwertertanz, bei dem der

Körper des Trancetänzers auf Schwertspitzen balancierte, ging ein zweiter Akteur in

Trance, der Fels wurde dem auf dem Boden Liegenden auf die Brust gelegt. Und mit einem

zweiten runden Flußstein zerschmetterte TG den Fels beim ersten Schlag, ohne den

Darunterliegenden zu verletzen.

Diesem Mahasiddha trauten seine

mittelalterlichen Zeitgenossen auch zu, daß er nichtrostendes Eisen erfunden hatte und

tonnenschwere Brücken über die breiten Himalayaströme schlagen konnte. Wann immer TG

eine neue Brücke begann, beschreibt sein Biograph Lochen Gyurme Dechen, zerstörten

Dämone nachts das Begonnene, und TG bannte sie durch sein Ritual oder auf andere

abenteuerliche Weise.

Am Sonntag, den 25. September 1988, hielten wir

die ersten Kettenglieder einer TG-Brücke in Tibet in unseren Händen. Wir hatten sie

gefunden "in der Nähe" eines überlieferten Ortes, an dem selbst wir keine

Brücke mehr fanden. Es waren die gleichen Eisenstücke wie in Bhutan, rötlich- bis

gelblich-braun, mit geschlossener Patina, eher wie Bronze als nach Eisen aussehend. Ich

sah die perfekt geschmiedeten Nähte, fast übergangslose Verschweißungen. Diese

schwächste Stelle war ihre Stärke. Eine metallurgische, vor Jahren schon gemachte

Untersuchung der Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule in Zürich an einem

bhutanesischen Kettenglied hatte erbracht, daß die Nähte arsenhaltig sind.

Willfried Epprecht schreibt: "Dies macht

es wahrscheinlich, daß das vorliegende Eisen aus kleinen Stücken etwas unterschiedlicher

Zusam-

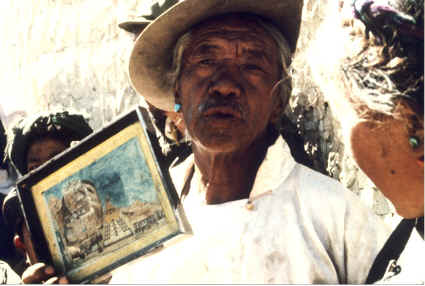

Das Bild, das dieser

Tibeter zu seinem wohlbehüteten Besitz zählt, zeigt den Tempel Cung Riwoche, wie er wohl

ausgesehen haben mag, bevor große Teile von ihm in der chinesischen Kulturrevolution

zerstört wurden. Links im Bild deutlich zu erkennen: die Eisenkettenbrücke Thang-stongs

über den Brahmaputra.

mensetzung und Korngröße zusammengeschmiedet

worden ist ... Sehr wahrscheinlich sind zuerst Stäbe hergestellt worden, die hierauf zu

Gliedern geformt und schließlich längs einer Schlußnaht (vielleicht am

Aufstellungsort?) zu Ringen geschlossen wurden ...". Und in näherer Beschreibung der

Nahtzone: "... Es scheint, als ob der schwer anätzbare Ferrit beim Feuerschweißen

ein flüssiger Film gewesen wäre, der die zu verbindenden Oberflächen mit all ihren

Unregelmäßigkeiten benetzte. Bemerkenswert ist dabei, daß auch Eisenflächen unter

Schlackenpartien mit der Sonderferrit-Haut bedeckt sind. Der beschriebene Nahtfilm hat

eine große Ähnlichkeit mit demjenigen, welchen G. Becker in einer römischen

Schwertklinge als Verbindungszone zwischen der gehärteten Stahlschneide und dem weicheren

Klingen-Hauptteil aus Eisen fand. Er stellte fest, daß die Verbindungszone einen

erheblich über 2,8 Prozent liegenden Arsengehalt besitzt. Aus diesem Grunde wurde eine

Mikrosonden-Prüfung der Ketten-Schweißnaht ausgeführt, ließ doch der gefundene

Arsengehalt eine ähnliche Schweißverbindung vermuten. Es ist tatsächlich eine

eindeutige Arsenkonzentration ... vorhanden."

Nach genauerer Beschreibung des Arsengehaltes

lesen wir weiter: "Schon Aristoteles soll die Leichtflüssigkeit gewisser Eisensorten

gekannt haben. Möglicherweise war damit arsenhaltiges Eisen gemeint. Bekannt ist auch,

daß arsenhaltiger Stahl besonders schlackenarm ist. Für das römische Schwert vermutet

G. Becker, daß die heiße Eisenklinge vor dem Anschmieden der Stahlschneiden mit flüssig

werdenden, niedrig schmelzenden Luppen aus arsenhaltigem Eisen benetzt worden sein

könnte. Eine entsprechende Technik ist auch bei der Herstellung der ,Montage-Naht' des

vorliegenden Kettenglieds denkbar. Vielleicht kommt auch eine andere Herstellungsart des

arsenreichen Schmelzfilms in Frage, zum Beispiel der Auftrag eines arsenhaltigen Pulvers

(Arsenoxid) oder einer Paste, welche beim Feuerschweißen schmolz und die Oberfläche des

Stücks filmartig benetzte." Solche Arsennähte sind uns nicht bekannt, außer bei

dem möglicherweise aus der Klingenmanufaktur von Damaskus stammenden römischen Schwert.

Daß wiederum historische Verbindungen zum tibetisch-asiatischen Raum, z. B. über die

Seidenstraße, im Spiel sein können, die das Schmiedegeheimnis dort hingebracht haben,

ist nicht auszuschließen. Wir wissen weiterhin auch aus der Biographie des Lochen Gyurme

Dechen, daß die Schmiede Paros einmal 7000 Kettenglieder für TG hergestellt hatten und

TG 1400 Traglasten, jede aus 15 Gliedern bestehend, zusammentrug. Ob diese Glieder einzeln

waren oder schon zu einem Kettenstück zusammengesetzt, wird nie erwähnt.

Woher auch immer TG diese Schmiedetechnik haben

mochte, ob in religiöser Eingebung empfangen oder von seinen rastlosen Reisen zwischen

Indien und dem chinesischen Kaiserhof kreuz und quer durch alle Länder des Himalaya

mitgebracht, sie ist eine Sensation, schon wenn man bedenkt, unter welchen Bedingungen

"auf dem Dach der Welt", dort, wo Holz selten und kostbar ist, am Holzkohlefeuer

in dieser Perfektion geschmiedet wurde. Über mögliche Vorbilder von

Hängebrückenkonstruktionen aus Eisenketten gibt es unterschiedliche, mehr oder weniger

unbewiesene Angaben. Der Engländer Joseph Needham erwähnt eine chinesische, die schon im

ersten Jahrhundert n. Chr. entstanden sein soll. und ausgerechnet um 1410 repariert wurde.

Es ist uns aber nicht bekannt, daß TG in Yünnan am Lantsang-Fluß gewesen sein könnte.

Auch am Euphrat und über den Mekong soll es frühe Kettenbrücken gegeben haben. Nur

historische Restketten hingen an den ersten drei Brücken TG's, die wir entdeckten;

moderne Stahlseile trugen die eigentliche Hängelast.

Die Ketten waren nurmehr Reliquiare. An den

beiden Ufern die aus Felsgestein gefügten Gründungen, immer wieder reparierte

Massierungen von Stein und Resten eines nahegelegenen zerstörten Klosters und der

tempelartigen, früheren Brückenkopfgebäude, wie wir sie von Chuwori und aus dem

heutigen Bhutan kennen. Wir fanden geschnitzte Holzpfeilerteile, Türschwellensteine und

ähnliche nach der Überlieferung segensreich aufgeladene Objekte in die Konstruktion

eingefügt. Und am diesseitigen Ufer lag ein weiblicher, großer, gerundeter Flußstein

mit einem dunklen "Fußabdruck" TG's, so wie es unzählige Fußabdrücke Buddhas

in der buddhistischen Welt geben soll. Und am jenseitigen Ufer das Pendant des anderen

Fußes nahe der Gründung der Ketten im Fels, an einem von Büschen überwucherten Relief

TG's. Zwischen den Fußabdrücken die Brücke, ein altes buddhistisches Symbol der

Befreiung: welch ein Bild, welch eine sprechende Situation, welch ein großer Schritt, den

TG hier getan hat.

In der Hitze des Spätsommermittags

untersuchten wir - kopfüber über dem reißenden Gebirgsfluß - jedes einzelne

Kettenglied nach Inzisionen und wurden fündig. Auf einem Glied stand, wohl im heißen

Zustand mit langem Meißel in das Metall getrieben und daher ein wenig ungelenk: Kostbare

Eisenbrücke. Ein Indiz für die Authentizität eines besonderen, eines heiligen Erbauers,

wenn nicht TG's selbst. Wenig später fanden wir an einer zweiten Brücke eine Jahreszahl,

das Wasser-Hund-Jahr. Aber welches? Nach dem 64-Jahre-Zyklus der Tibeter fällt diese

Angabe für die Lebenszeit TG's auf zwei Daten: einmal in seine frühe Kindheit, das

zweite zyklische Mal in sein 81. Lebensjahr, also 1442.

Und tatsächlich hat er hier in dieser Gegend

zu dieser Zeit eine seiner Brücken gebaut, wie seine Biographie angibt.

Später im September sollten wir noch

größeres Glück haben. Bei der Entdeckung des legendären, noch niemals vorher

dokumentierten wichtigsten Klosters TG's, Cung (oder Pal-) Riwoche am Tsangpo im

westlichen Zentraltibet, das wir nach tagelangen Irrfahrten durch Flußtäler fanden,

stand neben einem gewaltigen Stufentempel aus TG's Architektenhand die

"Bilderbuchbrücke", die wir uns in unseren kühnsten Träumen nicht vorgestellt

hatten.

Sie ist das Glanz- und Beweisstück seiner

Brückenbaukunst, Die Brücke von Cung (bzw. Pal) Riwoche aus dem Jahre 1436 ist aufgrund

einer der vielen Prophezeihungen Tibets ein Garant der Existenz des tibetischen

Buddhismus, solange sie existiert und verehrt wird; sie führt uns daher direkt ins

Mittelalter zurück. Wir fanden diese Prophezeihung durch Zufall in einer Nebenbemerkung

einer Chronik von Ladakh, nachdem wir wieder zurück in Berlin waren. Glücklicherweise

haben die rGyal-Pos, die Verwalter Riwoches, in den vergangenen Jahrhunderten ihr Erbe

verstanden und auch nach oder auch in der Kulturrevolution die Brücke geschützt bzw.

wiederhergestellt: sie ist in bestem Zustand für die rituelle Praxis. Denn für den

Übergang über den Brahmaputra, den Tsang-po, der hier bei normalem Wasserstand im Herbst

noch keine Hundert Meter breit ist, ist eine neue Stahlseilbrücke gebaut worden.

Kaum jemand versäumt es, an der geheiligten

Brücke TG's auch im Vorbeigehen zu opfern oder eine Ehrbezeugung zu machen. Je zwei

seitliche Eisenketten, etwa in Hüfthöhe eines Tibeters, werden mit weiteren Ketten in

Fußhöhe, auf denen Holzbohlen liegen, durch Yaklederstreifen, geflochtene, verstärkende

Lederriemen und Seile zusammengehalten; nicht selten hängen Tierfelle oder ganze Häute,

zum Beispiel eines Marders oder Jungtieres daran. Beim Begehen muß man den Rhythmus der

schwingenden Ketten aufnehmen, denn die "Geländer" sind nicht nur für uns zu

niedrig. Die Brücke überspannt in zwei Schritten den ruhig fließenden, großen Strom.

Der erste größere Schritt vom Steilufer, aus einem Opferchörten heraus, an dem frische

Blumen und immer die Gebetsfahnen, die "Wind-

Mit einem magischen, jetzt wiederentdeckten

Ritual, das auch heute noch in Spiti praktiziert wird, soll Thang-stong mit

übersinnlicher Kraft die Widerstände von Dämonen beim Bau seiner ersten Brücke

überwunden und die Bewohner der Stadt Lhasa vor einer Epidemie gerettet haben. Einem am

Boden liegenden Menschen wurde ein Fels, in dem sich der Dämon versteckt hielt, auf die

Brust gelegt, erzählt die Legende. Thang-stong zerschmetterte ihn mit einem magischen

Dolch, einem "Donnerkeil", gleich beim ersten Schlag, ohne den darunter

Liegenden zu verletzen.

Thang-stong, von den Tibetern wie ein

Heiliger verehrt, widmete sich der Medizin, bevor er sich dem Brückenbau

zuwandte. Skulpturen zeigen ihn deshalb immer mit zwei Gegenständen

in den Händen: In der rechten die Glieder einer Eisenkette, in der

linken ein Gefäß mit dem "Nektar des langen Lebens".

pferde", flattern, setzt ab auf einer

Anhäufung von Felsgestein im Fluß: Ausnutzung einer natürlichen Insel oder, wie wir

wissen, oft künstliche Setzung, ein Erkennungsmerkmal der Brücken TG's. Da beginnt der

zweite Brückenteil, meist ein wesentlich kürzerer. In Chuwori wie in Riwoche oder

Tsethang.

Vermutlich hat er 50 bis 60

Eisenkettenbrücken, 60 hölzerne und 118 Fähren bauen lassen, sagt die Chronik. Den

Brückenbau begann er erst im Alter. Vorher galt seine Aktivität anderen Aufgaben wie der

Architektur und der Medizin. Darum ist er immer abgebildet mit zwei kennzeichnenden

Gegenständen in den Händen: in der rechten die Glieder einer Eisenkette. in der linken

ein Gefäß mit dem Nektar des langen Lebens. Aber das sind andere, noch unerzählte

Geschichten. Im Hintergrund der Brücke steht eine der großartigsten Architekturen TG's,

der siebenstöckige Stufentempel mit Fresken (vermutlich) aus seiner Hand. Der

mandalaartige Grundriß des teils schwer zerstörten Heiligtums ist noch deutlich zu

erkennen. Der meterhohe Schutt der eingeschlagenen Dächer der vielen kleinen Kapellen in

den Stockwerken hat zum Glück die außergewöhnliche Ansammlung von Mandala-Fresken, im

unteren Teil der Wände und manchmal bis zu zwei Drittel Höhe hinauf, vor der Zerstörung

durch das strenge trockene Klima bewahrt. Wir photographierten den größten Teil der

zugänglichen Fresken und winzigen Kapellen erstmalig für die Kunstgeschichte und hoffen

heute, daß nicht inzwischen begonnene Reparaturen diesen Schatz von besonderer Qualität

zerstört haben. Denn dem Tibeter bedeutet die Authentizität weniger als die

Vollständigkeit und Vervollkommnung der heiligen Darstellungen. Erst in ihrer

Vollkommenheit werden sie wirksam. Darum übermalen sie sie gern.

Diese Expedition gab uns die Beweise, daß TG

die Persönlichkeit Tibets ist, die wir, die wir ihn mit Leonardo da Vinci verglichen, in

ihm vermutet hatten. Sein Universalismus war auf vielen Gebieten beispielhaft, nicht nur

auf dem des Brückenbaus. Die Strukturen seiner Weltsicht könnten heute wieder

beispielhaft werden - einer unserer Gründe, an dem teils von der Technischen Universität

Berlin finanzierten umfassenden Portrait von Thang-stong rGyal-po weiterzuarbeiten.

Wolf Kahlen

THANG-STONG RGYAL-PO - A LEONARDO OF TIBET

Wolf Kahlen

In 1985, while working

for the Royal Government of Bhutan as Consultant in Art and Architecture, travelling

freely within the country and making drawings, I started to trace the life and works of

Thang-stong rGyal-po. This genius and mahasiddha, whose name is familiar within the

Tibetan Himalayan world, remains virtually unknown among western scholars except for his

activity as a builder of iron bridges.

R. A. Stein was the

first scholar to undertake accurate research and to devote some of his energy to an

analysis and explanation of Thang-stong rGyal-po's importance. Cyrus Rembert Stearns and

Janet Gyatso, in 1980 and 1981 respectively, published works dealing exclusively with the

spiritual traditions and the life story of Thang-stong rGyal-po (henceforth abbreviated as

TG). Stearns, whom I met in early 1986, has since become engaged in my research and is

jointly responsible for the results I am able to present here. Emphasis is put on the

works of TG in different arts as seen by me as an artist in general.

In brief: TG lived 124

years, from 1361 to 1485; he was something of a Renaissance figure, who travelled most of

his life, while teaching, building, constructing, performing, painting, composing and

healing, among other activities. His methods of perceiving, reflecting and acting within

the world were extremely open-minded, interdisciplinary, intermediary, social and

«crazy» (grub-thob smyon-pa). He was in the first instance a sensuous and

pragmatic person, a bridge-builder in both a literal and a symbolic sense, bridging

numerous gaps in Tibet. For example he spanned the rift between social strata insofar as

he practised as a blacksmith, a lowly occupation, and at the same time acted as a

philosopher and reincarnated emanation (thugs-sprul) of Guru Padmasambhava. He

taught while shifting from one occupation to another, thereby condemning peoples'

prejudices about differences among sentient beings.

We consider TG, as

Janet Gyatso does, to be the example of a mahasiddha as an artist. He was an

architect who made an unrivalled and extraordinary contribution to the Tibetan

architectural heritage (Zlum-brtsegs Iha-khang at sPa-gro, Bhutan), a poet, a builder of

ferries and bridges (Icags-zam-pa), a composer, sculptor, painter, engineer,

physician, blacksmith and philosopher; he was also the founder and promoter of the A-Che

Iha-mo drama theatre and the originator of the purportedly lost ritual Pho-bar

rdo-gcog, the Breaking of the Stone, among other occupations. Many of his

activities may be compared with those of his contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci. In this

paper we shall omit his life-story, his role as a gter-ston, his reincarnations,

his spiritual traditions, his tantric and medicinal practices, his mahasiddha-powers and

legendary attributes, and concentrate instead on four groups of our discoveries: bridges,

architecture, frescoes and a ritual.

The results all were

obtained during the First International Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition, which I organised

in 1988 with partial support from the Technische Universität Berlin.

We would not have

discovered what we did without the preliminary work of Stearns, his thesis on TG's life in

general (1980) and his later final translation (n. d.) of the biography by Lo-chen

'Gyur-med bde-chen (1609) under the title King of the Empty Plain (Stearns 1980).

The expedition took place between August and October 1988. For financial reasons the

members were of various nationalities: the Polish expert in Buddhism and iconography Marek

Kalmus; the Polish anthropologist and second cameraman, Waldemar Czechowski; the Tibetan

Padma Wangyal; the American Cyrus Rembert Stearns as Tibetologist, and myself as artist,

film maker, initiator and leader of the expedition. For the purposes of the present paper

the route of the expedition may be summarised as follows: starting in lndia at Dharamsala

we travelled all over Spiti to Tabo, Kye, Lhalun, Kibber and the Pin Valley (names in

international transcription), to Kathmandu and Bodnath in Nepal, and then into Tibet to

'Bri-khung, bSam-yas, rTsed-thang, Zwha-lu, rGyal-rtse, gZhis-ka-rtse, sNye-thang,

'Bras-spungs, Lha-rtse, rNam-ring, Ri-bo-che and Ding-ri. Earlier theoretical and

practical research on the subject and the results from my work in Bhutan and Sikkim are

included here within the following. The results (given in specific examples):

1. The iron chain suspension bridge at

Yu-na, Yu-na Icags-zam.

2. The iron chain suspension bridge at

Ri-bo-che (this and Yu-na lcags-zam will serve as two examples of bridges).

3. The mchod-rten of gCung - resp.

dPal Ri-bo-che (as an example of architecture).

4. The frescoes of Ri-bo-che (as examples

of painting).

5. The ritual Pho-bar rdo-gcog (as

an example of the link between performance and theatre).

Illustrations1

of these examples are given in plates 1-8.

1. Yu-na lcags-zam2 (plate

1).

The bridge is located

in the upper sKyid-chu Valley north of Lhasa south of 'Bri-khung-mthil. The historic iron

chains span about 30 metres, but modern steel cables stabilise the bridge today. The

neighbouring monastery of Yu-na was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

Relics like carved wooden pillars, beams and stone reliefs are today embedded in the

foundations of the bridge on both sides of the stream. At either end of the bridge are

round boulders, bored through in order to house an iron bolt to which the chain was

fastened. These boulders may be either the original anchors or later replacements in the

traditional style. On two of the iron links we found incisions, representing inscriptions.

The rough quality of the letters testifies to the difficult process of producing them

during the red glowing phase of the hammering, rather than to the antiquity of the

structure. Technically, the inscription could only have been done with the use of a long

chisel, which would have given the craftsman sufficient distance to protect his hands from

the heat. Angling the chisel and forming the syllables must have been difficult, and the

legend is understandably simple.

Plate 1: Yu-na

Icags-zam, showing details of iron chain links and incision.

lt reads: rin-chen

Icags-zam, Precious or Valuable Iron Bridge. The term rin-chen, which is often

used, suggests that the bridge must have been made by, or in honour of, or in relation to

an important person, and/or must be situated at a holy place, etc. This is supported by

the other incision we found, which reads: khyi-chu (literally «dog water»). This

suggests a date, which, within the two Tibetan sixty-year calendar cycles corresponding to

the lifetime of TG, would represent either 1382 or 1442. In the first of these Water Dog

years TG would have been only twenty years old. Both inscriptions argue in favour of 1442:

TG did not start building bridges until he was sixty-nine years old, and, not

surprisingly, his biography states that he was active in this area of the upper skyid-chu

during precisely this time.

2. Ri-bo-che lcags-zam (plate 2)

Ri-bo-che monastery

(the name is usually prefixed with the expression gCung or dPal) - not to be

confused with Ri-bo-che in mDo-khams - was TG's main seat after Chu-bo-ri. The monastery

housed several thousand monks, and TG's followers lived here until its destruction. The

site, located at the ninety-degree bend of the gTsang-po River, south of rNam-ring in

dBus-gTsang, is dominated by a gorgeous seven-storey-high bKra-shis sgo-mang-type mchod-rten,

or sku-’bum, with a processional path (skor-lam) at the base,

completing the mandala-structure, and an iron chain bridge nearby. The stupa is the only

architectural structure which basically survived the ideologically-motivated destruction

here.

Plate 2: Ri-bo-che Icags-zam,

with the mchod-rten in the background

The bridge is a

childhood dream of a bridge. lt spans the river gTsang-po, which is no wider than 100

metres at this point, in two steps, a longer and a shorter suspending part. Typically of

TG's bridges (as we know from the biography's description of the building procedures at

rTse-thang and other places), the starting point was a pile of river stones, which were

already there or else assembled for the purpose. Yak-hide and leather thongs were fastened

to the links of the chain at either side. These hang down and support wooden planks and

logs, which constitute the floor of the bridge. The chains serve as handrails as well,

though they barely reach the height of one's hips. As we had expected, the bridge appears

to be more than 500 years old. According to the biography it was built in 1436, and it has

obviously occupied the same spot since. The foundations of the bridge on the banks are

crowned by ma-ni chu-skor, and enormous trunks of old willow trees are used within

the stone masonry work. The iron links themselves are of a standard form that I have

examined in Bhutan. They are one foot long, oblong shaped, more like squeezed ellipses,

covered by a bronze-like, smooth reddish-brown patina, with a particular diagonal seam

soldered with iron containing arsenic. Thus the seams, usually the weakest parts, are

reinforced and are free of any rust. The chains themselves are entirely free of

iron-moulds, probably as a result of the rather unclean composition of the blacksmithed

iron. The bridge is an object of private daily worship and religious service on the part

of the inhabitants of the village. Its perfect condition is no doubt to be explained by a

prophecy known to the villagers: Buddhism will flourish in Tibet as long as this holy

bridge remains. The bridge has accordingly been defended and taken care of over time. The

documentation we collected represents the first photographs, films and videotapes ever

made. Prior to this the only existing documentation was written. The only drawing was by

Peter Aufschnaiter3, who passed by the village more than forty years ago during

his escape, but did not dare to enter it. The bridge is just visible in the far left-hand

side of his drawing, next to the stupa architecture of Ri-bo-che.

Plate 3: Ri-bo-che

bKra-shis sgo-mang

3. The mchod-rten of

Ri-bo-che (plate 3)

This mchod-rten is

definitely by TG's hand. The construction process is described in detail in the biography.

lt is an edifice seven storeys high (if we count the visual structural elements from the

outside; seen from the interior we may add another storey, because of a double-storeyed bum-pa);

a three-dimensional mandala like the three sku-bum of rGyal-rtse, of rGyang

(with the construction of which TG is said to have helped), and of Jo-nang. The building

was erected between 1449 and 1456, with varying responses from the local inhabitants. lt

received strong support from the labourers and material supplies from the rNam-ring ruler;

but the construction also saw a period of severe resistance on the part of the workers, a

number of assassination attacks and thefts, and the collapse of certain walls. Wonderful

stories concerning building techniques, spiritual teachings connected with the labour, and

legends of the wild and crazy life of the mahasiddha accompanied the construction

process. After the mchod-rten's completion, even the Emperor of China sent loads of

presents for its consecration. (In this context, we should not neglect to mention TG's

most important and most innovative architectural accomplishment in Bhutan: Zlum-brtsegs

Iha-khang in the sPa-gro Valley. This is a mchod-rten built as a temple - something

that had never been previously done, as far as I know - showing the same interior features

in the basement as the Ri-bo-che sku-’bum. This floor is used only for

circumbulation. The bum-pa and the top floor contain resectively three and four

niches for altars. The exquisite sPa-gro shrine, which I visited several times, is too

complex to be described here, but it should nevertheless be compared with the Ri-bo-che mchod-rten.)

4. The frescoes of

Ri-bo-che (plates 4-5)

Within the very small

and narrow chapels of the two storeys above the basement (which is used for processional

circumbulation), we observed and documented frescoes, luckily preserved in their lower

sections. The rubble that fell from the massive wood, mud and slate roofs, during their

destruction in the recent past by the Red Guards, protected the murals from decay. The

frescoes are of very considerable interest; we believe them to be either by TG's own hand,

or else commissioned by him. lt is probable that they were at least in part

iconographically initiated and supervised by him. All the paintings on the second storey,

for example, are mandala-compositions. These are rare in Tibet, and represent a

significant feature of centres for higher tantric practices. The style of the paintings

varies between floral design in earthy colours and free-flowing, dark-outlined figures of

the same colour in material and character. Some of them have a transparent coating, and

the colours look different in bright light because of the slight gloss. We did not have

enough time to examine them for more than three days, which were fully occupied with the

documentation work. Further research on the frescoes should be carried out very soon,

since they are soon likely to vanish under the «restoration» work that has recently

started. On the strength of our experience as artists and researchers, we believe that the

frescoes may date back to the fifteenth century. The hand of the artist - or artists - is

very personal, and even quite daring within the given framework of the iconographic

regulations. There is an unpretentious, direct depiction of the necessary

Plate 4: Fresco in

«floral» style

Plate 5: Lower part of

mandala fresco (upper part destroyed)

features of the figures

which indicates a strong personality - a characteristic which can be attributed to TG

himself. While the work is incomparable to other schools, the character of the mandalas is

reminiscent of Ngor E-vam. Comparative research on the frescoes of Cang-sgang-kha in

Thim-phug, Bhutan, should also be carried out.

5. The Ritual Pho-bar

rdo-gcog (plates 6-8)

In the remote and

politically forbidden Indian border valley of Pin, in Spiti (Himachal Pradesh), we

discovered the Pho-bar rdo-gcog ritual, and recorded it in full with 16 mm film,

video, photographs and sound equipment. The origin of this ceremony, the «Breaking of the

Stone», is attributed to TG. lt was observed by Tibetologists over fifty years ago but

was since believed to have been lost. We agree with Stein's opinion that this ritual,

which is related to the Bon religion, is a link between the story-telling and lecturing

activities of the wandering ma-ni-pa, which I was able to observe in Bhutan, and

the Tibetan performances of A-Iche Iha-mo. With actors of Ri-bo-che, TG founded a school

that came to acquire considerable fame. This highly respected company usually performed

the first drama among a number of troupes during the «Yogurt festivals» held at the

Nor-bu gling-kha. There are reports by witnesses over the centuries. The historical

background of the three-hour ritual may be summarised briefly.

At the request of

Tsong-kha-pa, the story goes, TG is invited to Lhasa to help in quelling a severe

epidemic. Arriving miraculously on a white eagle, he identifies the cause of the disaster

variously as the demon dBang-rgyal, or Ha-la rTa-brgyad, or Drang-srong chen-po gzha'-bdud

(Rahula with the sea-snake, chu-srin), inside a stone that forms the threshold of

the Jo-khang door. He initiates and then performs the ceremony in the market place. The

sequence of events within the ritual is as follows: TG asks the demon to leave the stone;

he makes offerings to the demon; he reviles the demon and urges him more forcefully to

depart; then in order to convince the demon of the inferiority of his magic, TG

demonstrates his supernatural powers by balancing his body on the tips of swords. But he

is unable to elicit any reaction from the demon. Finally, TG announces that he will break

the boulder and thereby force the demon to appear in open light; he had better leave the

area. The rock, which requires two men to lift it, is placed on the chest of another

actor, in trance, lying on his back on the floor. The rock is struck with another

riverstone; if it breaks at the first blow, this signifies dharmakaya. lf it does

so at the second blow, this is taken as an omen for sambhogakaya, and at the third

as nirmanakaya. The solemnity of the ritual is interrupted at some point in the

introductory scenes for a historic «lecture» with a humorous beginning, and a deadly

fight at the end. (This story sheds light on an unexplained relationship between the King

of the North, Byang Mi-rgod rgyal-po, and the dharmaraja Chos-rgyal Nor-bzang. The

story could be based on the legend of TG building a mchod-rten at the Mongolian

border to prevent the infiltration of the Mongols. Surprisingly, we found the theme of

Nor-bzang depicted in the nearby Tabo monastery as a painting on the wall of the gtsug-lag-khang.

But this, and the possibility of a relationship with the ritual, requires closer

study.)

Before the ritual takes

place a travelling altar (mchod-bcams) bearing - in this case - two images of TG,

is set up. As is always the case before even modern A-che Iha-mo-performances, the initial

prayer is sung to TG, asking him to purify the space and situation. When we showed our bu-chen

people from Sagnam the text that Roerich had written down about sixty years ago with

the help of the lo-chen (lo-tsa-ba chen-po), the leader and main magician of

the troupe of married lamas, they could hardly hold back their tears: since this was

exactly the text of their grandfathers and great-grandfathers, used over the generations

and still employed in the initiation of the leader’s eldest son. We take this as

proof that we had found the same lineage of Pho-bar rdo-gcog performers. Neither in

bhutan nor in Tibet could I find either them or any other bu-chen.

Plate 6: The Pho-bar

rdo-gcog ritual: beginning of the sword dance

Plate 7: The Pho-bar

rdo-gcog ritual: bu-chen from Sagnam, Spiti

Plate 8: The Pho-bar

rdo-gcog ritual: the moment of breaking the stone

Our knowledge of all

the other diverse professional activities of TG that have been mentioned, but not

illustrated in the present paper, together with biographical details, enable us now to

give a fairly accurate picture of his works and life. This is in preparation as an

illustrated book and a video film portrait. We collected some eighty hours of video

documentation, three hours of 16 mm film and three thousand slides in order to edit a film

in eight parts.4 The first part, The demon in the rock, has been cut and

was shown for the first time during the present conference. It depicts only the search for

and the discovery and documentation of the entire Pho-bar rdo-gcog ceremony, of

wich I have been able to give just fragments here.

Notes

1. All photographs - 1988 Marek

Kalmus/Wolf Kahlen, TG-Archive, Berlin.

2. The spelling «Yu-na» corresponds to

the local pronunciation of the place, and may not represent the proper Tibetan

orthography.

3. For a picture see: Brauen, M. 1883. Peter

Aufschnaiter - Sein Leben in Tibet. Innsbruck: Steiger-Verlag.

4. Between 1988 and 1992 I have given

lectures and film presentations on the subject of TG in Bonn, Berlin, Beijing, Zürich,

Vienna, Budapest, Hamburg, Krakow, Munich, Basel, St. Petersburg, Riga.

References

Aris, M. V. 1979. Bhutan:

the early history of a Himalayan kingdom. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Epprecht, W. 1979.

Schweisseisen-Kettenbrücke aus dem 14. Jahrhundert in Bhutan (Himalaja) mit arsenreicher

Feuerschweissung. In Arch. Eisenhüttenwesen (Zürich) 50, 473-77.

Gyatso, J. 1981. A

literary transmission of the traditions of Thang-stong rGyal-po: a study of visionary

buddhism in Tibet. Berkeley: University of California.

'Gyur-med bde-chen. 1976

[1609]. dPal grub-pa’i dbang-phyug brtson-’grus bzang-po’i mam-par

thar-pa kun-gsal nor-bu’i me-Iong. Bir (Kangra, HP): Kandro/ Tibetan Kampa

Industrial Society.

Kahlen, W. 1990. Tibets

Leonardo. VDI-Nachrichten Magazine (Düsseldorf)

Nov. 1990, 90-98.

-----1990a. Der Dämon im

Stein. Wiederentdeckung eines mittelalterlichen Rituals im verborgenen Spiti. Junges

Tibet (Zürich) Sept. 1990, 44-49.

-----1990b. Der

Mahasiddha Thang-stong rGyal-po - ein Leonardo Tibets.

Dharma-Nektar (Mechernich)

3, 18-20.

-----1991 [in press]. Der

Dämon im Stein [provisional titlel]. Indo Asia. Stuttgart.

-----1988-1990. Der

Dämon im Stein. Video film, Low- and Highband U-Matic, 110 min., colour, 0-sound.

Edition Ruine der Künste Berlin 1988-91.

Peter of Greece and

Denmark. 1962. The ceremony of breaking the Stone. Folk. Dansk etnografisk

Tidsskrift 4, 65-70.

Roerich, G. N. 1932. The

ceremony of breaking the stone. Journal of Urusvati 2, 25-51.

Stearns, C. R. 1980. The

life and teachings of the Tibetan saint Thang-stong rGyal-po, «King of the Empty

Plain». Seattle: University of Washington.

----- n.d. King of the

Empty Plain. The life of the Tibetan mahasiddha Tangtong Gyalpo. Unpublished

translation of 'Gyur-med bde-chen 1976 [1609] (op. cit.).

Stein, R. A. 1956. L’Epopée

tibétaine de Gesar dans sa version lamaique de Ling. Paris.

-----1959. Recherches

sur I’épopée et la barde au Tibet. Paris.

F I E L D W 0 R K R E P 0 R T S

PL ISSN 0239-8818

HEMISPHERES

No. 9, 1994

Wolf Kahlen

THANG-STONG RGYAL-PO - A LEONARDO OF TIBET

In 1985 I served as consultant to the Royal Government of Bhutan for Art and Architecture. Travelling freely within the country and making drawings. I started to trace the life and works of Thang-stong rGyal-po, the genius Mahasiddha, whose name is known within the Tibetan Himalayas, but who remains virtually unknown among Western scholars, except for his accomplishments as builder of iron bridges. R. A. Stein was the only scholar who carried out research on Thang-stong rGyal-po and came to understand his importance. Janet Gyatso and Cyrus Rembert Stearns, in 1979 and 1980 respectively, published papers dealing either with the spiritual traditions or the life story of Thang-stong rGyal-po. Stearns, whom I met in early 1986, has since collaborated with me in my research and shares responsibility for the results I present here. In this report I emphasize the diverse artistic achievements of Thang-stong rGyal-po as seen by myself, also an artist.

Thang-stong rGyal-po was a Mahasiddha of Renaissance character, who in the course of his lifelong travels also engaged in teaching, building, constructing, performing, painting, composing, healing, etc. He lived 124 years, from 1361-1485. His methods of perceiving, acting and reflecting within the world were strategically open-minded, interdisciplinary, intermediary, social and crazy (grub-thob smyon-pa) because he was in the first instance a sensuous and pragmatic person, an actual builder as well as a symbolic one, bridging gaps in Tibetan society, such as the one between the 'classes'. He practiced as a blacksmith, thus adhering to a 'lower' class, and at the same time acted as a philosopher, teacher and reincarnated emanation (thugs-sprul) of Guru Padmasambhava. By trespassing from one 'profession' upon another, he could show up common prejudices about differences between sentient beings.

We consider Thang-stong rGyal-po, as Janet Gyatso does, as the example of a Mahasiddha as artist. In addition to his unrivaled contribution to Tibetan architecture (zlum-brtsegs IHa-khang at sPa-gro, Bhutan); he was also a poet, bridge and ferry builder, composer, sculptor, painter, engineer, physican, blacksmith, philosopher, the founder and promoter of the A-lche-IHamo drama theatre and the originator of the seemingly lost ritual of Breaking the Stone (pho-bar rdo-gcog). Many of his activities may be compared with those of his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci. In this report we exclude his life-story, his aspect as a gTer-ton, his reincarnations, his spiritual traditions, his Tantric and medicinal practices, his mahasiddha-powers and legendary aspects, and concentrate on four of his activities that we investigated in the Himalayas: bridge building, architecture, frescos and ritual enactments - the results of which were displayed at the First International Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition organized by me in 1988 with the support of the Technische Universität Berlin. The expedition took place from August till October 1988. The members came from different national backgrounds: a Polish expert on Buddhism and iconography, Mark Kalmus, a Polish anthropologist and second cameraman. Waldemar Czechowski, a Tibetan Padma Wangyal, an American Tibetologist Cyrus Rembert Stearns and myself as artist, film maker, initiator and leader of the expedition.

The route of the expedition, as far as the results given here are concerned, was as follows. Starting in India at Dharamsala we travelled around Spiti to Tabo, Kye, Lhalun, Kibber and the Pin-valley (names in the international transcription), then to Kathmandu and Bodhath in Nepal, then into Tibet to Brikhung, bSam-yas, rTse-thang, Zwha-lu, rGyal-rtse, gZhis-ka-tse, sNye-thang, Bras-spungs, Lha-rtse, rNam-ring, Ribo-che and Ding-ri. In this brief report comments are offered on only five of the works of Thang-stong rGyal-po that we encountered: 1. the iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na; 2. the iron chain suspension bridge at Ri-bo-che; 3. the mchod-rten of gCung-resp. Pal Ri-boche as an example of architecture: 4. the frescoes of Ri-bo-che as an example of painting; and 5. the ritual pho-bar rdo-gcog as an example of the link between performance and theater.

We would not have discovered what we did, without the prelimary work of Stearns, his thesis on Thang-stong rGyal-po's life (1980) and his translation of the biography Lo-chen Gyur-med bde-chen (1609) under the title King of the Emply Plain (1989).

The iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na

The spelling Yu-na follows local pronunciation. The bridge is located in the upper sKyid-chu-valley, north of LHa-sa, south of Bri-khung til. The historic iron chains span about 30 meters, but contemporary steel cables stabilize the bridge today. The neighbouring former monastery of Yu-na was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Relics, such as carved wooden pillars, beams and stone reliefs, are embedded today in the foundations on both sides of the stream. Round boulders with central holes for the suspension of the chains with an iron bolt at either side seem to be original or are indistinguishable from traditional designs. On two of the iron links we found incisions.

The roughness of the inscriptions are probably more a sign of the difficult process of producing them during the red glowing phase of the hammering rather than a sign of age. Technically, the inscription could only have been accomplished by use of a long chisel, which gave enough distance to protect the hands from the heat. The pointing of the chisel and the configuration of the syllables must have been difficult. Therefore the characters are simple and read: rin-chen lCzags-zam, Treasurable or Valuable Iron Bridge. The often used term rin-chen denotes that the bridge must be made by, in honor of, or related to an important person, and/or must be situated at a holy place, etc.

The other incision we found supports this, saying: khyi-chu, dog-water, thus giving a date which could be the year 1442 in the Tibetan 60-year calendar cycle, if we consider the life time of Thang-stong rGyal-po relevant. The first dog-water-year would be the time when he was only about twenty years old, the next one is the assumed date, and the last one some time after his death. Both inscriptions give us reason to take the date 1442 as correct since Thang-stong rGyal-po did not start bridge-building until he was 69 years old. Not surprisingly, his biography mentions his activity in this area of the upper sKyid-chu right at that time.

The iron chain suspension bridge Ri-bo-che

The Ri-bo-che monastery, called gCung-or Pal Ri-bo-che, not to be mixed up with Ri-bo-che in do-Khams, was, in addition to Chu-bo-ri. Thang-stong rGyal-po's main seat. Here several thousands of monks lived and Thang-stong rGyal-po's followers stayed until its destruction. The site at the 90 degree bend of the gTsang-po river, south of rNam-ring in U-Tsang, is dominated (and this is the only architectural structure which survived the ideological 'purification' intact) by a gorgeous seven-storey-high bKra-shis sgo-mang-type mchod-rten or sku-bum with a professional path skor-lam at the base, completing the mandala structure, and an iron-chain-bridge nearby.

The bridge is a childhood dream of a bridge. It bridges the river gTsang-po, here in the upper part not wider than 100 meters, in two steps, a longer and shorter suspending part, as it is usual with Thang-stong rGyal-po's bridges, starting on a pile of river stones, originally found there or piled up, as Thang-stong rGyal-po did at rTse-thang and other places, mentioned in his biography. Yakhide and leatherstrings, which are fastened to the links of the chain at either side, hang down and loop under wooden planks and logs, which function as foot paths. The chains serve as handrails as well, though they reach the height of one's hips. According to the biography, the bridge was build in 1436; and as we anticipated, it looks its 550 years. The foundations of the bridge at the river side are crowned by ma-ni chu-skor, and enormous trunks of old willow trees are used within the stone masonry work. The iron links themselves are of the expected and known type that I have examined in Bhutan. They are one foot long, oblong shaped, more like squeezed ellipses, covered by a bronze-like smooth brownish to reddish patina, with a particular diagonal solding seam of arsenic-containing iron. Therefore the seams, usually the weakest part, are of additional strength and free of any rust, as the chains are entirely free of iron-mould, probably as a result of the rather unclean composition of the blacksmithed iron.

The perfect condition of the bridge, which is an object of private daily worship and religious service by the inhabitants of the village, finds its explanation, no doubt, in one of the prophecies known in the region: Buddism will flourish in Tibet as long as this holy bridge stays. Thus the bridge has been defended and taken care of down through the centuries.

The documentation we took are the first photographs, films and videotapes ever. There is no other visual record of the bridge, apart from a sketch made more than forty years ago by Peter Aufschnaiter, passing by the village on his escape, not daring to enter it. The bridge can be seen at the very left of his drawing next to the stupa of Ri-bo-che.

The mchod-rten of Ri-bo-che

The mchod-rten is definitely of Thang-stong rGyal-po's hand, the construction pro-cess is described in detail in the biography. It is a seven-story-high hierarchical structure, if we count the structurally visual elements from the outside. Seen from the interior, we may add another storey inside the double-storeyed bum-pa and a threedimensional mandala like the three sku-bum of rGyal-rtse, rGyang (this one Thangstong rGyal-po is said to have helped building), and Jo-nang. The building was erected between 1449 and 1456 with the active support of the rNam-ring ruler who provided labourers and materials. There was also several resistance by the workers, several assassination attempts, thefts and some collapses of walls. Wonderful stories concerning building techniques, spiritual teachings connected with the labour, and legends of the wild and crazy life of the Mahasiddha are told. After the mchod-rten's completion even the Emperor of China sent loads of presents to its consecration.

In this context we should also mention the most important and most innovational architecture of Thang-stong rGyal-po in Bhutan, the IZlum-brtsegs IHa-khang in the sPagro-valley, showing some of the same inside features as the Ri-bo-che sku-bum. To the best of my knowledge, the construction of a mchod-rten as a temple did not occur before the time of Thang-stong rGyal-po.

The frescoes of Ri-bo-che

Within the very small and narrow chapels of the two storeys above the basement, used for processional circumambulation, we observed and documented frescoes, luckily preserved in their lower parts. The rubble that fell from the massive wood, mud and slate roves, when they had been destroyed by the Red Guards, protected the murals from decay. The frescoes are of great interest and, we believe, of Thang-stong rGyal-po's own hand, or commissioned by him. They were probably, at least in part, iconographically initiated and supervised by him. All the paintings of the second storey, for example, are mandala-compostions, a rarity in Tibet, and a significant attribute of centres for higher level-Tantric practices.

The style of the painting is not uniform; floral design in earthy colors and free-flowing, differ from heavily dark outlined figures of the same colour in material and character. Some of them have a transparent coating and the colours look different in brightness because of the slight gloss. We did not have enough time to examine them in the three days of our visit, which were filled with documentation work. They have to be urgently researched before they vanish under new frescoes, for 'restoration' work has already started. I may say here that we believe from our experience as artists and researchers that the frescoes may date from as early as the 15th century. The artist's or artists' 'hand' is very personal, even quite daring within the given framework of the iconographic regulations. It is a way of unpretentious, direct representation of the necessary features of the figures, which proves the strong personality(ies) of the artist(s), a characteristic which can be attributed to Thang-stong rGyal-po himself. We may only say there is a certain relationship to Ngor-Evam, as far as the mandala-character is concerned.

The ritual Pho-bar rdo-gcog

We found the ritual of breaking of the stone (pho-bar rdo-gcog) attributed to Thangstong-rGyal-po, in the lonely and politically forbidden Indian border-valley Pin of Spiti in Himachal Pradesh. This ritual, which was believed lost forever after having been first observed by Tibetologists over fifty years ago, was recorded in full with 16 mm film, video, photography and audio equipment. We agree with Stein that this bon-related ritual is link between the story-telling and lecturing activities of the wandering ma-ni-pa, which I observed in Bhutan, and the Tibetan performances of A-lche-IHa-mo. With actors of Ri-bo-che. Thang-stong rGyal-po founded a school of such fame that according to witnesses they usually enacted the first drama among the various troupes at the Nor-bu glingkha-yoghurt-festivals.

The abbreviated historical background of the three hour-long ritual can be given as follows. By request of Tsong-kha-pa, so the story goes. Thang-stong rGyal-po is asked to come to IHa-sa to help cure a severe epidemic. He arrives, miraculously flying on a white eagle, and finds the cause of the disaster to be either the demon dBang-rgyal, or Hala rTa-brgyad or Drang-srong chen-po gzha-bDud (Rahula with the sea-snake chu-srin) inside a stone at the threshold of the Jo-khang door. He initiates and then performs the ceremony on the market-place. The stages of the ritual are: asking the demon to leave the stone, then making an offering to him, then blaming him and urging him to go, and finally demonstrating one's superior supernatural powers to the evil force by balancing his body on the tips of swords. Thang-stong rGyal-po is not able to have the demon react at all. So he announces he will break the boulder and force the demon to appear in open light. The threats have no effect, so Thang-stong rGyal-po must do what he threatens. The rock, which requires two men to lift, is placed on the chest of the third actor, lying in trance on his back on the floor. lf the stone breaks by the first stroke of another riverstone, the omen is dharmakaya; by the second, nirmanakaya, etc.

The tone of the ritual is somewhat interrupted in the introductory scenes by a historical 'lecture' that begins humorously and ends with a deadly fight. The lecture sheds light on the unexplained relation between the 'King of the North' byang mi-rgod rGyal-po and the dharmaraja Chos-rGyal Nor-bzang, a story which could stem from the legend of Thang-stong rGyal-po building a mchod-rten at the northern border to prevent Mongolian infiltration. Surprisingly, we found a Nor-bzang theme depicted in the nearby Tabo monastery on the tsug IHa-Khang-wall. But this, and its possible relation to the ritual, still has to be examined closely.

Before the ritual takes place a travelling altar mchod-bcams, in this case with two Thang-stong rGyal-po statues, is set up and A-Iche IHa-mo-performances, the initial

prayer is sung to Thang-stong rGyal-po, asking him to purify the site, space and situation.

When we showed our bu-chen-people from Sagnam the text Roerich had written down about 60 years ago with the help of the lo-tsa-ba chen-po, the lo-chen leader and main magician of the troupe of married lamas, they could hardly back their tears. This was their grandfather's and great grandfather's text, used over the generations and even now given further for the initiation of the leader's eldest son. This we take as a proof of having found the same lineage of pho-bar rdo-gcog-performers. Neither in Bhutan nor in Tibet could I find them or other bu-chen.

Our knowledge of the other diverse professional activities of Thang-stong rGyal-po and of his life story, which for reasons of space cannot be illustrated here, enables us now to give an exact picture of his works and life. A privately financed archive has been established in Berlin in order to collect and popularize information on this Tibetan genius. We took some eighty hours of video documentation, three hours of 16 mm film and three thousand slides in the course of the expedition, but we are still looking for more photos, audio- and videotapes, films, literary sources and quotes, ritual and profane objects connected with his Tantric practices, etc. An illustrated book and videofilm portrait is in preparation; and a film in eight parts has been planned. The first part, entitled 'The Demon in the Rock' and depicting the search for and discovery of the 'breaking of the stone' ritual, has already been cut.

Please help us trace additional materials by sending your information to: Thang-stong rGyal-po Archiv Berlin, Prof. Wolf Kahlen, Ehrenbergstraße 11, 14195 Berlin, Germany (Tel 030-831 37 08).

References

Aris, Michael 1979. Bhutan - The Early History of a Himalayan Kingdom. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Epprecht, Wilfried 1979. Schweisseisen-Kettenbrucke aus dem 14. Jahrhundert in Bhutan (Himalaya) mit arsenreicher Feuerschweissung. In Arch. Eisenhuttenwesen 50. Nr. 11. 473-477. Zürich: ETH Zürich, Mitteilung aus dem Institut fur Metallforschung.

Gyatso, Janet 1981. A Literary Transmission of the Traditions of Thang-stong rGyal-po: A Study of Visionary Buddhism in Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

'Gyur-med bde-chen. 1609. dPla grub-pa'i dbang-phyug brtson-’grus bzang-pa'i rnam-par thar pa kun-gsal nor-bu'i me-Iong. Kandro: Tibetan Kampa Industrial Society, P.O.Bir, Distr. Kangra, Himachal Pradesh; India, 1976.

Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark 1962. The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone. Folk, 4, 65-70.

Roerich, Georges N. 1932. The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone. Journal of Urusvati. Himalayan Research Institute, 2, 4, 25-51.

Steams, Cyrus Rembert. 1980. The Life and Teachings of the Tibetan Saint Thang-stong rGyal-po, 'King of the Empty Plain'. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- 1989. King of the Empty Plain. The Life of the Tibetan Mahasiddha Tangtong Gyalpo. Unpublished translation of Gyur-med bde-chen.

Stein, R. A. 1956. L'Epopeé tibétaine de Gesar dans sa version lamaique de Ling. Paris.

- 1959. Recherches sur I'épopeé et le barde au Tibet. Paris.

TOPICAL REPORTS

Thang-stong rGyal-po - A Leonardo of Tibet

Wolf Kahlen

In 1985 I served as consultant to the Royal Government of Bhutan for Art and Architecture. Travelling freely within the country and making drawings, I started to trace the life and works of Thang-stong rGyal-po, the genius Mahasiddha, whose name is known within the Tibetan Himalayas, but who remains virtually unknown among western scholars, except for his accomplishments as builder of iron bridges. R. A. Stein was the only scholar who carried out research on Thang-stong rGyal-po and came to understand his importance. Janet Gyatso and Cyrus Rembert Stearns, in 1979 and 1980 respectively, published papers dealing either with the spiritual traditions or the life story of Thang-stong rGyal-po. Stearns, whom I met in early 1986, has since collaborated with me in my research and shares responsibility for the results I present here. In this report I emphasize the diverse artistic achievements of Thang-stong rGyal-po as seen by myself, also an artist.

Thang-stong rGyal-po was a Mahisiddha of renaissance character, who in the course of his lifelong travels also engaged in teaching, building, constructing, performing, painting, composing, healing, etc. He lived 124 years, from 1361-1485. His methods of perceiving, acting and reflecting within the world were strategically openminded, interdisciplinary, intermediary, social and 'crazy' (grub-thob smyon-pa) because he was in the first instance a sensuous and pragmatic person, an actual bridge builder as well as a symbolic one, bridging gaps in Tibetan society, such as the one between the 'classes'. He practiced as a blacksmith, thus adhering to a 'lower' class, and at the same time acted as a philosopher, teacher and reincarnated emanation (thugs-sprul) of Guru Padmasambhava. By trespassing from one 'profession' upon another, he could showed up common prejudices about differences between sentient beings.

We consider Thang-stong rGyal-po, as Janet Gyatso does, as the example of a Mahisiddha as artist. In addition to his unrivaled contribution to Tibetan architecture (zlum-brtsegs IHa-khang at sPa-gro, Bhutan); he was also a poet, bridge and ferry builder, composer, sculptor, painter, engineer, physican, blacksmith, philosopher, the founder and promoter of the A-Iche-IHamo drama theatre and the originator of the seemingly lost ritual of Breaking the Stone (pho-bar rdo-gcog). Many of his activities may be compared with those of his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci. In this report we exclude his life-story, his aspect as a gTer-gon, his reincarnations, his spiritual traditions, his tantric and medicinal practices, his mahisiddha-powers and legendary aspects and concentrate on four of his activities that we investigated in the Himalayas: bridge building, architecture, frescos and ritual enactments - the results of which were displayed at the First International Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition organized by me in 1988 with the support of the Technische Universität Berlin.

The expedition took place from August till October 1988. The members came from different national backgrounds: the Polish expert on Buddhism and iconography Marek Kalmus, the Polish anthropologist and second cameraman, Waldemar Czechowski, the Tibetan Padma Wangyal, the American tibetologist Cyrus Rembert Stearns and myself as artist, film maker, initiator and leader of the expedition.

The route of the expedition, as far as the results given here are concerned, was as follows. Starting in lndia at Dharamsala we travelled around Spiti to Tabo, Kye, Lhalun, Kibber and the Pin-valley (names in international transcription), then to Kathmandu and Bodhath in Nepal, then into Tibet to 'Brikhung, bSam-yas, rTse-thang, Zwha-lu, rGyal-rtse, gZhis-ka-tse, sNye-thang, Bras-spungs, Lha-rtse, rNam-ring, Ribo-che and Ding-ri. In this brief report comments are offered on only five of the works of Thang-stong rGyal-po that we encountered: 1. the iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na; 2. the iron chain suspension bridge at Ri-bo-che, 3. the mchod-rten of gCung- resp. Pal Ri-bo-che as an example of architecture; 4. the frescoes of Ri-bo-che as an example of painting; and 5. the ritual pho-bar rdo-gcog as an example of the link between performance and theater.

We would not have discovered what we did, without the prelimary work of Stearns, his thesis on Thang-stong rGyal-po's life (1980) and his translation of the biography Lo-chen 'Gyur-med bde-chen (1609) under the title (1989)

The iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na

The spelling Yu-na follows local pronunciation. The bridge is located in the upper sKyid-chu - valley north of LHa-sa south of 'Bri-khung til. The historic iron chains span about 30 meters, but contemporary steel cables stabilize the bridge today. The neighbouring former monastery of Yu-na was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Relics, such as carved wooden pillars, beams and stone reliefs, are embedded today in the foundations on both sides of the stream. Round boulders with central holes for the suspension of the chains with an iron bolt at either side seem to be original or are indistinquishable from traditional designs. On two of the iron links we found incisions.

The roughness of the inscriptions are probably more a sign of the difficult process of producing them during the red glowing phase of the hammering rather than a sign of age. Technically the inscription could only have been accomplished by use of a long chisel, which gave enough distance to protect the hands from the heat. The pointing of the chisel and the configuration oft he syllables must have been difficult. Therefore the characters are simple and read: rinchen lCzags-zam, Treasurable or Valuable lron Bridge. The often used term rin-chen denotes that the bridge must be made by, in honor of, or related to an important person, and/or must be situated at a holy place, etc.

The other incision we found supports this, saying: khyi-chu, dogwater, thus giving a date which could be the year 1442 within the Tibetan 60-year calendar cycle, if we consider the life time of Thang-stong rGyal-po relevant. Within his life the first dog-water-year would be the time, when he was only about twenty years old, the next one is the assumed date and the last one some time after his death. Both inscriptions give us reason to trust in the date 1442, since Thang-stong rGyal-po did not start bridge-building until he was 69 years old. Not surprisingly his biography mentions his activity in this area of the upper sKyid-chu right during that time.

The iron chain suspension bridge Ri-bo-che

Ri-bo-che monastery, called gCung-or Pal Ri-bo-che, not to be mixed up with Ri-bo-che in do-Khams, was, in addition to Chu-bo-ri, Thang-stong rGyal-po's main seat. Here several thousands of monks lived and Thang-stong rGyal-po's followers stayed until its destruction. The site at the 90 degree bend of the gTsang-po river, south of rNam-ring in U-Tsang, is dominated (and this is the only architectural structure which survived the ideological ‘purification' in tact) by a gorgeous seven-storey-high bKra-shis sgo-mang-type mchod-rten or sku-bum with a professional path skor-lam at the base, completing the mandala structure, and an iron-chain-bridge nearby.

The bridge is a childhood dream of a bridge. lt bridges the river gTsang-po, here in the upper part not wider than 100 meters, in two steps, a longer and shorter suspending part, as usual with Thang-stong rGyal-po's bridges, starting on a pile of river stones, originally found there or piled up, as Thangstong rGyal-po did at rTse-thang and other places, mentioned in his biography. Yakhide and leatherstrings, which are fastened to the links of the chain at either side, hang down and loop under wooden planks and logs, which function as foot paths. The chains serve as handrails as well, though they reach the height of one's hips. According to the biography the bridge was built in 1436; and as we anticipated, it looks its 550 years. The foundations of the bridge at the river side are crowned by ma-ni chu-skor and enormous trunks of old willow trees are used within the stone masonry work. The iron links themselves are the expected and known type that I have examined in Bhutan. They are one foot long, oblong shaped, more like squeezed ellipses, covered by a bronze-like smooth brownish to reddish patina, with a particular diagonal solding seam of arsenic-containing iron. Therefore the seams, usually the weakest part, are of additional strength and free of any rust, as the chains are entirely free of iron-mould, probably as a result of the rather unclean composition of the blacksmithed iron.

The perfect condition of the bridge which is an object of private daily worship and religious service by the inhabitants of the village finds its explanation, no doubt, in one of the prophecies known in the region: Buddhism will flourish in Tibet as long as this holy bridge stays. Thus the bridge has been defended and taken care of down through the centuries.