songs

mahasiddha

iron chain bridge

architecture

sculpture

poetry

medicine

painting

philosophy

theater

Bhutan

Mongolia

Spiti

in general

THANG-STONG RGYAL-PO - A LEONARDO OF TIBET

Wolf Kahlen

In 1985, while working

for the Royal Government of Bhutan as Consultant in Art and Architecture, travelling

freely within the country and making drawings, I started to trace the life and works of

Thang-stong rGyal-po. This genius and mahasiddha, whose name is familiar within the

Tibetan Himalayan world, remains virtually unknown among western scholars except for his

activity as a builder of iron bridges.

R. A. Stein was the

first scholar to undertake accurate research and to devote some of his energy to an

analysis and explanation of Thang-stong rGyal-po's importance. Cyrus Rembert Stearns and

Janet Gyatso, in 1980 and 1981 respectively, published works dealing exclusively with the

spiritual traditions and the life story of Thang-stong rGyal-po (henceforth abbreviated as

TG). Stearns, whom I met in early 1986, has since become engaged in my research and is

jointly responsible for the results I am able to present here. Emphasis is put on the

works of TG in different arts as seen by me as an artist in general.

In brief: TG lived 124

years, from 1361 to 1485; he was something of a Renaissance figure, who travelled most of

his life, while teaching, building, constructing, performing, painting, composing and

healing, among other activities. His methods of perceiving, reflecting and acting within

the world were extremely open-minded, interdisciplinary, intermediary, social and

«crazy» (grub-thob smyon-pa). He was in the first instance a sensuous and

pragmatic person, a bridge-builder in both a literal and a symbolic sense, bridging

numerous gaps in Tibet. For example he spanned the rift between social strata insofar as

he practised as a blacksmith, a lowly occupation, and at the same time acted as a

philosopher and reincarnated emanation (thugs-sprul) of Guru Padmasambhava. He

taught while shifting from one occupation to another, thereby condemning peoples'

prejudices about differences among sentient beings.

We consider TG, as

Janet Gyatso does, to be the example of a mahasiddha as an artist. He was an

architect who made an unrivalled and extraordinary contribution to the Tibetan

architectural heritage (Zlum-brtsegs Iha-khang at sPa-gro, Bhutan), a poet, a builder of

ferries and bridges (Icags-zam-pa), a composer, sculptor, painter, engineer,

physician, blacksmith and philosopher; he was also the founder and promoter of the A-Che

Iha-mo drama theatre and the originator of the purportedly lost ritual Pho-bar

rdo-gcog, the Breaking of the Stone, among other occupations. Many of his

activities may be compared with those of his contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci. In this

paper we shall omit his life-story, his role as a gter-ston, his reincarnations,

his spiritual traditions, his tantric and medicinal practices, his mahasiddha-powers and

legendary attributes, and concentrate instead on four groups of our discoveries: bridges,

architecture, frescoes and a ritual.

The results all were

obtained during the First International Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition, which I organised

in 1988 with partial support from the Technische Universität Berlin.

We would not have

discovered what we did without the preliminary work of Stearns, his thesis on TG's life in

general (1980) and his later final translation (n. d.) of the biography by Lo-chen

'Gyur-med bde-chen (1609) under the title King of the Empty Plain (Stearns 1980).

The expedition took place between August and October 1988. For financial reasons the

members were of various nationalities: the Polish expert in Buddhism and iconography Marek

Kalmus; the Polish anthropologist and second cameraman, Waldemar Czechowski; the Tibetan

Padma Wangyal; the American Cyrus Rembert Stearns as Tibetologist, and myself as artist,

film maker, initiator and leader of the expedition. For the purposes of the present paper

the route of the expedition may be summarised as follows: starting in lndia at Dharamsala

we travelled all over Spiti to Tabo, Kye, Lhalun, Kibber and the Pin Valley (names in

international transcription), to Kathmandu and Bodnath in Nepal, and then into Tibet to

'Bri-khung, bSam-yas, rTsed-thang, Zwha-lu, rGyal-rtse, gZhis-ka-rtse, sNye-thang,

'Bras-spungs, Lha-rtse, rNam-ring, Ri-bo-che and Ding-ri. Earlier theoretical and

practical research on the subject and the results from my work in Bhutan and Sikkim are

included here within the following. The results (given in specific examples):

1. The iron chain suspension bridge at

Yu-na, Yu-na Icags-zam.

2. The iron chain suspension bridge at

Ri-bo-che (this and Yu-na lcags-zam will serve as two examples of bridges).

3. The mchod-rten of gCung - resp.

dPal Ri-bo-che (as an example of architecture).

4. The frescoes of Ri-bo-che (as examples

of painting).

5. The ritual Pho-bar rdo-gcog (as

an example of the link between performance and theatre).

Illustrations1

of these examples are given in plates 1-8.

1. Yu-na lcags-zam2 (plate

1).

The bridge is located

in the upper sKyid-chu Valley north of Lhasa south of 'Bri-khung-mthil. The historic iron

chains span about 30 metres, but modern steel cables stabilise the bridge today. The

neighbouring monastery of Yu-na was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

Relics like carved wooden pillars, beams and stone reliefs are today embedded in the

foundations of the bridge on both sides of the stream. At either end of the bridge are

round boulders, bored through in order to house an iron bolt to which the chain was

fastened. These boulders may be either the original anchors or later replacements in the

traditional style. On two of the iron links we found incisions, representing inscriptions.

The rough quality of the letters testifies to the difficult process of producing them

during the red glowing phase of the hammering, rather than to the antiquity of the

structure. Technically, the inscription could only have been done with the use of a long

chisel, which would have given the craftsman sufficient distance to protect his hands from

the heat. Angling the chisel and forming the syllables must have been difficult, and the

legend is understandably simple.

Plate 1: Yu-na

Icags-zam, showing details of iron chain links and incision.

lt reads: rin-chen

Icags-zam, Precious or Valuable Iron Bridge. The term rin-chen, which is often

used, suggests that the bridge must have been made by, or in honour of, or in relation to

an important person, and/or must be situated at a holy place, etc. This is supported by

the other incision we found, which reads: khyi-chu (literally «dog water»). This

suggests a date, which, within the two Tibetan sixty-year calendar cycles corresponding to

the lifetime of TG, would represent either 1382 or 1442. In the first of these Water Dog

years TG would have been only twenty years old. Both inscriptions argue in favour of 1442:

TG did not start building bridges until he was sixty-nine years old, and, not

surprisingly, his biography states that he was active in this area of the upper skyid-chu

during precisely this time.

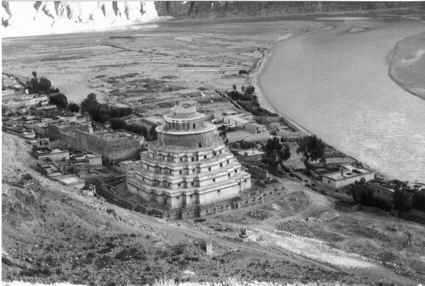

2. Ri-bo-che lcags-zam (plate 2)

Ri-bo-che monastery

(the name is usually prefixed with the expression gCung or dPal) - not to be

confused with Ri-bo-che in mDo-khams - was TG's main seat after Chu-bo-ri. The monastery

housed several thousand monks, and TG's followers lived here until its destruction. The

site, located at the ninety-degree bend of the gTsang-po River, south of rNam-ring in

dBus-gTsang, is dominated by a gorgeous seven-storey-high bKra-shis sgo-mang-type mchod-rten,

or sku-’bum, with a processional path (skor-lam) at the base,

completing the mandala-structure, and an iron chain bridge nearby. The stupa is the only

architectural structure which basically survived the ideologically-motivated destruction

here.

Plate 2: Ri-bo-che Icags-zam,

with the mchod-rten in the background

The bridge is a

childhood dream of a bridge. lt spans the river gTsang-po, which is no wider than 100

metres at this point, in two steps, a longer and a shorter suspending part. Typically of

TG's bridges (as we know from the biography's description of the building procedures at

rTse-thang and other places), the starting point was a pile of river stones, which were

already there or else assembled for the purpose. Yak-hide and leather thongs were fastened

to the links of the chain at either side. These hang down and support wooden planks and

logs, which constitute the floor of the bridge. The chains serve as handrails as well,

though they barely reach the height of one's hips. As we had expected, the bridge appears

to be more than 500 years old. According to the biography it was built in 1436, and it has

obviously occupied the same spot since. The foundations of the bridge on the banks are

crowned by ma-ni chu-skor, and enormous trunks of old willow trees are used within

the stone masonry work. The iron links themselves are of a standard form that I have

examined in Bhutan. They are one foot long, oblong shaped, more like squeezed ellipses,

covered by a bronze-like, smooth reddish-brown patina, with a particular diagonal seam

soldered with iron containing arsenic. Thus the seams, usually the weakest parts, are

reinforced and are free of any rust. The chains themselves are entirely free of

iron-moulds, probably as a result of the rather unclean composition of the blacksmithed

iron. The bridge is an object of private daily worship and religious service on the part

of the inhabitants of the village. Its perfect condition is no doubt to be explained by a

prophecy known to the villagers: Buddhism will flourish in Tibet as long as this holy

bridge remains. The bridge has accordingly been defended and taken care of over time. The

documentation we collected represents the first photographs, films and videotapes ever

made. Prior to this the only existing documentation was written. The only drawing was by

Peter Aufschnaiter3, who passed by the village more than forty years ago during

his escape, but did not dare to enter it. The bridge is just visible in the far left-hand

side of his drawing, next to the stupa architecture of Ri-bo-che.

Plate 3: Ri-bo-che

bKra-shis sgo-mang

3. The mchod-rten of

Ri-bo-che (plate 3)

This mchod-rten is

definitely by TG's hand. The construction process is described in detail in the biography.

lt is an edifice seven storeys high (if we count the visual structural elements from the

outside; seen from the interior we may add another storey, because of a double-storeyed bum-pa);

a three-dimensional mandala like the three sku-bum of rGyal-rtse, of rGyang

(with the construction of which TG is said to have helped), and of Jo-nang. The building

was erected between 1449 and 1456, with varying responses from the local inhabitants. lt

received strong support from the labourers and material supplies from the rNam-ring ruler;

but the construction also saw a period of severe resistance on the part of the workers, a

number of assassination attacks and thefts, and the collapse of certain walls. Wonderful

stories concerning building techniques, spiritual teachings connected with the labour, and

legends of the wild and crazy life of the mahasiddha accompanied the construction

process. After the mchod-rten's completion, even the Emperor of China sent loads of

presents for its consecration. (In this context, we should not neglect to mention TG's

most important and most innovative architectural accomplishment in Bhutan: Zlum-brtsegs

Iha-khang in the sPa-gro Valley. This is a mchod-rten built as a temple - something

that had never been previously done, as far as I know - showing the same interior features

in the basement as the Ri-bo-che sku-’bum. This floor is used only for

circumbulation. The bum-pa and the top floor contain resectively three and four

niches for altars. The exquisite sPa-gro shrine, which I visited several times, is too

complex to be described here, but it should nevertheless be compared with the Ri-bo-che mchod-rten.)

4. The frescoes of

Ri-bo-che (plates 4-5)

Within the very small

and narrow chapels of the two storeys above the basement (which is used for processional

circumbulation), we observed and documented frescoes, luckily preserved in their lower

sections. The rubble that fell from the massive wood, mud and slate roofs, during their

destruction in the recent past by the Red Guards, protected the murals from decay. The

frescoes are of very considerable interest; we believe them to be either by TG's own hand,

or else commissioned by him. lt is probable that they were at least in part

iconographically initiated and supervised by him. All the paintings on the second storey,

for example, are mandala-compositions. These are rare in Tibet, and represent a

significant feature of centres for higher tantric practices. The style of the paintings

varies between floral design in earthy colours and free-flowing, dark-outlined figures of

the same colour in material and character. Some of them have a transparent coating, and

the colours look different in bright light because of the slight gloss. We did not have

enough time to examine them for more than three days, which were fully occupied with the

documentation work. Further research on the frescoes should be carried out very soon,

since they are soon likely to vanish under the «restoration» work that has recently

started. On the strength of our experience as artists and researchers, we believe that the

frescoes may date back to the fifteenth century. The hand of the artist - or artists - is

very personal, and even quite daring within the given framework of the iconographic

regulations. There is an unpretentious, direct depiction of the necessary

Plate 4: Fresco in

«floral» style

Plate 5: Lower part of

mandala fresco (upper part destroyed)

features of the figures

which indicates a strong personality - a characteristic which can be attributed to TG

himself. While the work is incomparable to other schools, the character of the mandalas is

reminiscent of Ngor E-vam. Comparative research on the frescoes of Cang-sgang-kha in

Thim-phug, Bhutan, should also be carried out.

5. The Ritual Pho-bar

rdo-gcog (plates 6-8)

In the remote and

politically forbidden Indian border valley of Pin, in Spiti (Himachal Pradesh), we

discovered the Pho-bar rdo-gcog ritual, and recorded it in full with 16 mm film,

video, photographs and sound equipment. The origin of this ceremony, the «Breaking of the

Stone», is attributed to TG. lt was observed by Tibetologists over fifty years ago but

was since believed to have been lost. We agree with Stein's opinion that this ritual,

which is related to the Bon religion, is a link between the story-telling and lecturing

activities of the wandering ma-ni-pa, which I was able to observe in Bhutan, and

the Tibetan performances of A-Iche Iha-mo. With actors of Ri-bo-che, TG founded a school

that came to acquire considerable fame. This highly respected company usually performed

the first drama among a number of troupes during the «Yogurt festivals» held at the

Nor-bu gling-kha. There are reports by witnesses over the centuries. The historical

background of the three-hour ritual may be summarised briefly.

At the request of

Tsong-kha-pa, the story goes, TG is invited to Lhasa to help in quelling a severe

epidemic. Arriving miraculously on a white eagle, he identifies the cause of the disaster

variously as the demon dBang-rgyal, or Ha-la rTa-brgyad, or Drang-srong chen-po gzha'-bdud

(Rahula with the sea-snake, chu-srin), inside a stone that forms the threshold of

the Jo-khang door. He initiates and then performs the ceremony in the market place. The

sequence of events within the ritual is as follows: TG asks the demon to leave the stone;

he makes offerings to the demon; he reviles the demon and urges him more forcefully to

depart; then in order to convince the demon of the inferiority of his magic, TG

demonstrates his supernatural powers by balancing his body on the tips of swords. But he

is unable to elicit any reaction from the demon. Finally, TG announces that he will break

the boulder and thereby force the demon to appear in open light; he had better leave the

area. The rock, which requires two men to lift it, is placed on the chest of another

actor, in trance, lying on his back on the floor. The rock is struck with another

riverstone; if it breaks at the first blow, this signifies dharmakaya. lf it does

so at the second blow, this is taken as an omen for sambhogakaya, and at the third

as nirmanakaya. The solemnity of the ritual is interrupted at some point in the

introductory scenes for a historic «lecture» with a humorous beginning, and a deadly

fight at the end. (This story sheds light on an unexplained relationship between the King

of the North, Byang Mi-rgod rgyal-po, and the dharmaraja Chos-rgyal Nor-bzang. The

story could be based on the legend of TG building a mchod-rten at the Mongolian

border to prevent the infiltration of the Mongols. Surprisingly, we found the theme of

Nor-bzang depicted in the nearby Tabo monastery as a painting on the wall of the gtsug-lag-khang.

But this, and the possibility of a relationship with the ritual, requires closer

study.)

Before the ritual takes

place a travelling altar (mchod-bcams) bearing - in this case - two images of TG,

is set up. As is always the case before even modern A-che Iha-mo-performances, the initial

prayer is sung to TG, asking him to purify the space and situation. When we showed our bu-chen

people from Sagnam the text that Roerich had written down about sixty years ago with

the help of the lo-chen (lo-tsa-ba chen-po), the leader and main magician of

the troupe of married lamas, they could hardly hold back their tears: since this was

exactly the text of their grandfathers and great-grandfathers, used over the generations

and still employed in the initiation of the leader’s eldest son. We take this as

proof that we had found the same lineage of Pho-bar rdo-gcog performers. Neither in

bhutan nor in Tibet could I find either them or any other bu-chen.

Plate 6: The Pho-bar

rdo-gcog ritual: beginning of the sword dance

Plate 7: The Pho-bar

rdo-gcog ritual: bu-chen from Sagnam, Spiti

Plate 8: The Pho-bar

rdo-gcog ritual: the moment of breaking the stone

Our knowledge of all

the other diverse professional activities of TG that have been mentioned, but not

illustrated in the present paper, together with biographical details, enable us now to

give a fairly accurate picture of his works and life. This is in preparation as an

illustrated book and a video film portrait. We collected some eighty hours of video

documentation, three hours of 16 mm film and three thousand slides in order to edit a film

in eight parts.4 The first part, The demon in the rock, has been cut and

was shown for the first time during the present conference. It depicts only the search for

and the discovery and documentation of the entire Pho-bar rdo-gcog ceremony, of

wich I have been able to give just fragments here.

Notes

1. All photographs - 1988 Marek

Kalmus/Wolf Kahlen, TG-Archive, Berlin.

2. The spelling «Yu-na» corresponds to

the local pronunciation of the place, and may not represent the proper Tibetan

orthography.

3. For a picture see: Brauen, M. 1883. Peter

Aufschnaiter - Sein Leben in Tibet. Innsbruck: Steiger-Verlag.

4. Between 1988 and 1992 I have given

lectures and film presentations on the subject of TG in Bonn, Berlin, Beijing, Zürich,

Vienna, Budapest, Hamburg, Krakow, Munich, Basel, St. Petersburg, Riga.

References

Aris, M. V. 1979. Bhutan:

the early history of a Himalayan kingdom. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Epprecht, W. 1979.

Schweisseisen-Kettenbrücke aus dem 14. Jahrhundert in Bhutan (Himalaja) mit arsenreicher

Feuerschweissung. In Arch. Eisenhüttenwesen (Zürich) 50, 473-77.

Gyatso, J. 1981. A

literary transmission of the traditions of Thang-stong rGyal-po: a study of visionary

buddhism in Tibet. Berkeley: University of California.

'Gyur-med bde-chen. 1976

[1609]. dPal grub-pa’i dbang-phyug brtson-’grus bzang-po’i mam-par

thar-pa kun-gsal nor-bu’i me-Iong. Bir (Kangra, HP): Kandro/ Tibetan Kampa

Industrial Society.

Kahlen, W. 1990. Tibets

Leonardo. VDI-Nachrichten Magazine (Düsseldorf)

Nov. 1990, 90-98.

-----1990a. Der Dämon im

Stein. Wiederentdeckung eines mittelalterlichen Rituals im verborgenen Spiti. Junges

Tibet (Zürich) Sept. 1990, 44-49.

-----1990b. Der

Mahasiddha Thang-stong rGyal-po - ein Leonardo Tibets.

Dharma-Nektar (Mechernich)

3, 18-20.

-----1991 [in press]. Der

Dämon im Stein [provisional titlel]. Indo Asia. Stuttgart.

-----1988-1990. Der

Dämon im Stein. Video film, Low- and Highband U-Matic, 110 min., colour, 0-sound.

Edition Ruine der Künste Berlin 1988-91.

Peter of Greece and

Denmark. 1962. The ceremony of breaking the Stone. Folk. Dansk etnografisk

Tidsskrift 4, 65-70.

Roerich, G. N. 1932. The

ceremony of breaking the stone. Journal of Urusvati 2, 25-51.

Stearns, C. R. 1980. The

life and teachings of the Tibetan saint Thang-stong rGyal-po, «King of the Empty

Plain». Seattle: University of Washington.

----- n.d. King of the

Empty Plain. The life of the Tibetan mahasiddha Tangtong Gyalpo. Unpublished

translation of 'Gyur-med bde-chen 1976 [1609] (op. cit.).

Stein, R. A. 1956. L’Epopée

tibétaine de Gesar dans sa version lamaique de Ling. Paris.

-----1959. Recherches

sur I’épopée et la barde au Tibet. Paris.

F I E L D W 0 R K R E P 0 R T S

PL ISSN 0239-8818 HEMISPHERES No. 9, 1994

Wolf Kahlen

THANG-STONG RGYAL-PO - A LEONARDO OF TIBET

In 1985 I served as consultant to the Royal Government of Bhutan for Art and Architecture. Travelling freely within the country and making drawings. I started to trace the life and works of Thang-stong rGyal-po, the genius Mahasiddha, whose name is known within the Tibetan Himalayas, but who remains virtually unknown among Western scholars, except for his accomplishments as builder of iron bridges. R. A. Stein was the only scholar who carried out research on Thang-stong rGyal-po and came to understand his importance. Janet Gyatso and Cyrus Rembert Stearns, in 1979 and 1980 respectively, published papers dealing either with the spiritual traditions or the life story of Thang-stong rGyal-po. Stearns, whom I met in early 1986, has since collaborated with me in my research and shares responsibility for the results I present here. In this report I emphasize the diverse artistic achievements of Thang-stong rGyal-po as seen by myself, also an artist.

Thang-stong rGyal-po was a Mahasiddha of Renaissance character, who in the course of his lifelong travels also engaged in teaching, building, constructing, performing, painting, composing, healing, etc. He lived 124 years, from 1361-1485. His methods of perceiving, acting and reflecting within the world were strategically open-minded, interdisciplinary, intermediary, social and crazy (grub-thob smyon-pa) because he was in the first instance a sensuous and pragmatic person, an actual builder as well as a symbolic one, bridging gaps in Tibetan society, such as the one between the 'classes'. He practiced as a blacksmith, thus adhering to a 'lower' class, and at the same time acted as a philosopher, teacher and reincarnated emanation (thugs-sprul) of Guru Padmasambhava. By trespassing from one 'profession' upon another, he could show up common prejudices about differences between sentient beings.

We consider Thang-stong rGyal-po, as Janet Gyatso does, as the example of a Mahasiddha as artist. In addition to his unrivaled contribution to Tibetan architecture (zlum-brtsegs IHa-khang at sPa-gro, Bhutan); he was also a poet, bridge and ferry builder, composer, sculptor, painter, engineer, physican, blacksmith, philosopher, the founder and promoter of the A-lche-IHamo drama theatre and the originator of the seemingly lost ritual of Breaking the Stone (pho-bar rdo-gcog). Many of his activities may be compared with those of his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci. In this report we exclude his life-story, his aspect as a gTer-ton, his reincarnations, his spiritual traditions, his Tantric and medicinal practices, his mahasiddha-powers and legendary aspects, and concentrate on four of his activities that we investigated in the Himalayas: bridge building, architecture, frescos and ritual enactments - the results of which were displayed at the First International Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition organized by me in 1988 with the support of the Technische Universität Berlin. The expedition took place from August till October 1988. The members came from different national backgrounds: a Polish expert on Buddhism and iconography, Mark Kalmus, a Polish anthropologist and second cameraman. Waldemar Czechowski, a Tibetan Padma Wangyal, an American Tibetologist Cyrus Rembert Stearns and myself as artist, film maker, initiator and leader of the expedition.

The route of the expedition, as far as the results given here are concerned, was as follows. Starting in India at Dharamsala we travelled around Spiti to Tabo, Kye, Lhalun, Kibber and the Pin-valley (names in the international transcription), then to Kathmandu and Bodhath in Nepal, then into Tibet to Brikhung, bSam-yas, rTse-thang, Zwha-lu, rGyal-rtse, gZhis-ka-tse, sNye-thang, Bras-spungs, Lha-rtse, rNam-ring, Ribo-che and Ding-ri. In this brief report comments are offered on only five of the works of Thang-stong rGyal-po that we encountered: 1. the iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na; 2. the iron chain suspension bridge at Ri-bo-che; 3. the mchod-rten of gCung-resp. Pal Ri-boche as an example of architecture: 4. the frescoes of Ri-bo-che as an example of painting; and 5. the ritual pho-bar rdo-gcog as an example of the link between performance and theater.

We would not have discovered what we did, without the prelimary work of Stearns, his thesis on Thang-stong rGyal-po's life (1980) and his translation of the biography Lo-chen Gyur-med bde-chen (1609) under the title King of the Emply Plain (1989).

The iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na

The spelling Yu-na follows local pronunciation. The bridge is located in the upper sKyid-chu-valley, north of LHa-sa, south of Bri-khung til. The historic iron chains span about 30 meters, but contemporary steel cables stabilize the bridge today. The neighbouring former monastery of Yu-na was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Relics, such as carved wooden pillars, beams and stone reliefs, are embedded today in the foundations on both sides of the stream. Round boulders with central holes for the suspension of the chains with an iron bolt at either side seem to be original or are indistinguishable from traditional designs. On two of the iron links we found incisions.

The roughness of the inscriptions are probably more a sign of the difficult process of producing them during the red glowing phase of the hammering rather than a sign of age. Technically, the inscription could only have been accomplished by use of a long chisel, which gave enough distance to protect the hands from the heat. The pointing of the chisel and the configuration of the syllables must have been difficult. Therefore the characters are simple and read: rin-chen lCzags-zam, Treasurable or Valuable Iron Bridge. The often used term rin-chen denotes that the bridge must be made by, in honor of, or related to an important person, and/or must be situated at a holy place, etc.

The other incision we found supports this, saying: khyi-chu, dog-water, thus giving a date which could be the year 1442 in the Tibetan 60-year calendar cycle, if we consider the life time of Thang-stong rGyal-po relevant. The first dog-water-year would be the time when he was only about twenty years old, the next one is the assumed date, and the last one some time after his death. Both inscriptions give us reason to take the date 1442 as correct since Thang-stong rGyal-po did not start bridge-building until he was 69 years old. Not surprisingly, his biography mentions his activity in this area of the upper sKyid-chu right at that time.

The iron chain suspension bridge Ri-bo-che

The Ri-bo-che monastery, called gCung-or Pal Ri-bo-che, not to be mixed up with Ri-bo-che in do-Khams, was, in addition to Chu-bo-ri. Thang-stong rGyal-po's main seat. Here several thousands of monks lived and Thang-stong rGyal-po's followers stayed until its destruction. The site at the 90 degree bend of the gTsang-po river, south of rNam-ring in U-Tsang, is dominated (and this is the only architectural structure which survived the ideological 'purification' intact) by a gorgeous seven-storey-high bKra-shis sgo-mang-type mchod-rten or sku-bum with a professional path skor-lam at the base, completing the mandala structure, and an iron-chain-bridge nearby.

The bridge is a childhood dream of a bridge. It bridges the river gTsang-po, here in the upper part not wider than 100 meters, in two steps, a longer and shorter suspending part, as it is usual with Thang-stong rGyal-po's bridges, starting on a pile of river stones, originally found there or piled up, as Thang-stong rGyal-po did at rTse-thang and other places, mentioned in his biography. Yakhide and leatherstrings, which are fastened to the links of the chain at either side, hang down and loop under wooden planks and logs, which function as foot paths. The chains serve as handrails as well, though they reach the height of one's hips. According to the biography, the bridge was build in 1436; and as we anticipated, it looks its 550 years. The foundations of the bridge at the river side are crowned by ma-ni chu-skor, and enormous trunks of old willow trees are used within the stone masonry work. The iron links themselves are of the expected and known type that I have examined in Bhutan. They are one foot long, oblong shaped, more like squeezed ellipses, covered by a bronze-like smooth brownish to reddish patina, with a particular diagonal solding seam of arsenic-containing iron. Therefore the seams, usually the weakest part, are of additional strength and free of any rust, as the chains are entirely free of iron-mould, probably as a result of the rather unclean composition of the blacksmithed iron.

The perfect condition of the bridge, which is an object of private daily worship and religious service by the inhabitants of the village, finds its explanation, no doubt, in one of the prophecies known in the region: Buddism will flourish in Tibet as long as this holy bridge stays. Thus the bridge has been defended and taken care of down through the centuries.

The documentation we took are the first photographs, films and videotapes ever. There is no other visual record of the bridge, apart from a sketch made more than forty years ago by Peter Aufschnaiter, passing by the village on his escape, not daring to enter it. The bridge can be seen at the very left of his drawing next to the stupa of Ri-bo-che.

The mchod-rten of Ri-bo-che

The mchod-rten is definitely of Thang-stong rGyal-po's hand, the construction pro-cess is described in detail in the biography. It is a seven-story-high hierarchical structure, if we count the structurally visual elements from the outside. Seen from the interior, we may add another storey inside the double-storeyed bum-pa and a threedimensional mandala like the three sku-bum of rGyal-rtse, rGyang (this one Thangstong rGyal-po is said to have helped building), and Jo-nang. The building was erected between 1449 and 1456 with the active support of the rNam-ring ruler who provided labourers and materials. There was also several resistance by the workers, several assassination attempts, thefts and some collapses of walls. Wonderful stories concerning building techniques, spiritual teachings connected with the labour, and legends of the wild and crazy life of the Mahasiddha are told. After the mchod-rten's completion even the Emperor of China sent loads of presents to its consecration.

In this context we should also mention the most important and most innovational architecture of Thang-stong rGyal-po in Bhutan, the IZlum-brtsegs IHa-khang in the sPagro-valley, showing some of the same inside features as the Ri-bo-che sku-bum. To the best of my knowledge, the construction of a mchod-rten as a temple did not occur before the time of Thang-stong rGyal-po.

The frescoes of Ri-bo-che

Within the very small and narrow chapels of the two storeys above the basement, used for processional circumambulation, we observed and documented frescoes, luckily preserved in their lower parts. The rubble that fell from the massive wood, mud and slate roves, when they had been destroyed by the Red Guards, protected the murals from decay. The frescoes are of great interest and, we believe, of Thang-stong rGyal-po's own hand, or commissioned by him. They were probably, at least in part, iconographically initiated and supervised by him. All the paintings of the second storey, for example, are mandala-compostions, a rarity in Tibet, and a significant attribute of centres for higher level-Tantric practices.

The style of the painting is not uniform; floral design in earthy colors and free-flowing, differ from heavily dark outlined figures of the same colour in material and character. Some of them have a transparent coating and the colours look different in brightness because of the slight gloss. We did not have enough time to examine them in the three days of our visit, which were filled with documentation work. They have to be urgently researched before they vanish under new frescoes, for 'restoration' work has already started. I may say here that we believe from our experience as artists and researchers that the frescoes may date from as early as the 15th century. The artist's or artists' 'hand' is very personal, even quite daring within the given framework of the iconographic regulations. It is a way of unpretentious, direct representation of the necessary features of the figures, which proves the strong personality(ies) of the artist(s), a characteristic which can be attributed to Thang-stong rGyal-po himself. We may only say there is a certain relationship to Ngor-Evam, as far as the mandala-character is concerned.

The ritual Pho-bar rdo-gcog

We found the ritual of breaking of the stone (pho-bar rdo-gcog) attributed to Thangstong-rGyal-po, in the lonely and politically forbidden Indian border-valley Pin of Spiti in Himachal Pradesh. This ritual, which was believed lost forever after having been first observed by Tibetologists over fifty years ago, was recorded in full with 16 mm film, video, photography and audio equipment. We agree with Stein that this bon-related ritual is link between the story-telling and lecturing activities of the wandering ma-ni-pa, which I observed in Bhutan, and the Tibetan performances of A-lche-IHa-mo. With actors of Ri-bo-che. Thang-stong rGyal-po founded a school of such fame that according to witnesses they usually enacted the first drama among the various troupes at the Nor-bu glingkha-yoghurt-festivals.

The abbreviated historical background of the three hour-long ritual can be given as follows. By request of Tsong-kha-pa, so the story goes. Thang-stong rGyal-po is asked to come to IHa-sa to help cure a severe epidemic. He arrives, miraculously flying on a white eagle, and finds the cause of the disaster to be either the demon dBang-rgyal, or Hala rTa-brgyad or Drang-srong chen-po gzha-bDud (Rahula with the sea-snake chu-srin) inside a stone at the threshold of the Jo-khang door. He initiates and then performs the ceremony on the market-place. The stages of the ritual are: asking the demon to leave the stone, then making an offering to him, then blaming him and urging him to go, and finally demonstrating one's superior supernatural powers to the evil force by balancing his body on the tips of swords. Thang-stong rGyal-po is not able to have the demon react at all. So he announces he will break the boulder and force the demon to appear in open light. The threats have no effect, so Thang-stong rGyal-po must do what he threatens. The rock, which requires two men to lift, is placed on the chest of the third actor, lying in trance on his back on the floor. lf the stone breaks by the first stroke of another riverstone, the omen is dharmakaya; by the second, nirmanakaya, etc.

The tone of the ritual is somewhat interrupted in the introductory scenes by a historical 'lecture' that begins humorously and ends with a deadly fight. The lecture sheds light on the unexplained relation between the 'King of the North' byang mi-rgod rGyal-po and the dharmaraja Chos-rGyal Nor-bzang, a story which could stem from the legend of Thang-stong rGyal-po building a mchod-rten at the northern border to prevent Mongolian infiltration. Surprisingly, we found a Nor-bzang theme depicted in the nearby Tabo monastery on the tsug IHa-Khang-wall. But this, and its possible relation to the ritual, still has to be examined closely.

Before the ritual takes place a travelling altar mchod-bcams, in this case with two Thang-stong rGyal-po statues, is set up and A-Iche IHa-mo-performances, the initial

prayer is sung to Thang-stong rGyal-po, asking him to purify the site, space and situation.

When we showed our bu-chen-people from Sagnam the text Roerich had written down about 60 years ago with the help of the lo-tsa-ba chen-po, the lo-chen leader and main magician of the troupe of married lamas, they could hardly back their tears. This was their grandfather's and great grandfather's text, used over the generations and even now given further for the initiation of the leader's eldest son. This we take as a proof of having found the same lineage of pho-bar rdo-gcog-performers. Neither in Bhutan nor in Tibet could I find them or other bu-chen.

Our knowledge of the other diverse professional activities of Thang-stong rGyal-po and of his life story, which for reasons of space cannot be illustrated here, enables us now to give an exact picture of his works and life. A privately financed archive has been established in Berlin in order to collect and popularize information on this Tibetan genius. We took some eighty hours of video documentation, three hours of 16 mm film and three thousand slides in the course of the expedition, but we are still looking for more photos, audio- and videotapes, films, literary sources and quotes, ritual and profane objects connected with his Tantric practices, etc. An illustrated book and videofilm portrait is in preparation; and a film in eight parts has been planned. The first part, entitled 'The Demon in the Rock' and depicting the search for and discovery of the 'breaking of the stone' ritual, has already been cut.

Please help us trace additional materials by sending your information to: Thang-stong rGyal-po Archiv Berlin, Prof. Wolf Kahlen, Ehrenbergstraße 11, 14195 Berlin, Germany (Tel 030-831 37 08).

References

Aris, Michael 1979. Bhutan - The Early History of a Himalayan Kingdom. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Epprecht, Wilfried 1979. Schweisseisen-Kettenbrucke aus dem 14. Jahrhundert in Bhutan (Himalaya) mit arsenreicher Feuerschweissung. In Arch. Eisenhuttenwesen 50. Nr. 11. 473-477. Zürich: ETH Zürich, Mitteilung aus dem Institut fur Metallforschung.

Gyatso, Janet 1981. A Literary Transmission of the Traditions of Thang-stong rGyal-po: A Study of Visionary Buddhism in Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

'Gyur-med bde-chen. 1609. dPla grub-pa'i dbang-phyug brtson-’grus bzang-pa'i rnam-par thar pa kun-gsal nor-bu'i me-Iong. Kandro: Tibetan Kampa Industrial Society, P.O.Bir, Distr. Kangra, Himachal Pradesh; India, 1976.

Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark 1962. The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone. Folk, 4, 65-70.

Roerich, Georges N. 1932. The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone. Journal of Urusvati. Himalayan Research Institute, 2, 4, 25-51.

Steams, Cyrus Rembert. 1980. The Life and Teachings of the Tibetan Saint Thang-stong rGyal-po, 'King of the Empty Plain'. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- 1989. King of the Empty Plain. The Life of the Tibetan Mahasiddha Tangtong Gyalpo. Unpublished translation of Gyur-med bde-chen.

Stein, R. A. 1956. L'Epopeé tibétaine de Gesar dans sa version lamaique de Ling. Paris.

- 1959. Recherches sur I'épopeé et le barde au Tibet. Paris.

TOPICAL REPORTS

Thang-stong rGyal-po - A Leonardo of Tibet

Wolf Kahlen

In 1985 I served as consultant to the Royal Government of Bhutan for Art and Architecture. Travelling freely within the country and making drawings, I started to trace the life and works of Thang-stong rGyal-po, the genius Mahasiddha, whose name is known within the Tibetan Himalayas, but who remains virtually unknown among western scholars, except for his accomplishments as builder of iron bridges. R. A. Stein was the only scholar who carried out research on Thang-stong rGyal-po and came to understand his importance. Janet Gyatso and Cyrus Rembert Stearns, in 1979 and 1980 respectively, published papers dealing either with the spiritual traditions or the life story of Thang-stong rGyal-po. Stearns, whom I met in early 1986, has since collaborated with me in my research and shares responsibility for the results I present here. In this report I emphasize the diverse artistic achievements of Thang-stong rGyal-po as seen by myself, also an artist.

Thang-stong rGyal-po was a Mahisiddha of renaissance character, who in the course of his lifelong travels also engaged in teaching, building, constructing, performing, painting, composing, healing, etc. He lived 124 years, from 1361-1485. His methods of perceiving, acting and reflecting within the world were strategically openminded, interdisciplinary, intermediary, social and 'crazy' (grub-thob smyon-pa) because he was in the first instance a sensuous and pragmatic person, an actual bridge builder as well as a symbolic one, bridging gaps in Tibetan society, such as the one between the 'classes'. He practiced as a blacksmith, thus adhering to a 'lower' class, and at the same time acted as a philosopher, teacher and reincarnated emanation (thugs-sprul) of Guru Padmasambhava. By trespassing from one 'profession' upon another, he could showed up common prejudices about differences between sentient beings.

We consider Thang-stong rGyal-po, as Janet Gyatso does, as the example of a Mahisiddha as artist. In addition to his unrivaled contribution to Tibetan architecture (zlum-brtsegs IHa-khang at sPa-gro, Bhutan); he was also a poet, bridge and ferry builder, composer, sculptor, painter, engineer, physican, blacksmith, philosopher, the founder and promoter of the A-Iche-IHamo drama theatre and the originator of the seemingly lost ritual of Breaking the Stone (pho-bar rdo-gcog). Many of his activities may be compared with those of his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci. In this report we exclude his life-story, his aspect as a gTer-gon, his reincarnations, his spiritual traditions, his tantric and medicinal practices, his mahisiddha-powers and legendary aspects and concentrate on four of his activities that we investigated in the Himalayas: bridge building, architecture, frescos and ritual enactments - the results of which were displayed at the First International Thang-stong rGyal-po Expedition organized by me in 1988 with the support of the Technische Universität Berlin.

The expedition took place from August till October 1988. The members came from different national backgrounds: the Polish expert on Buddhism and iconography Marek Kalmus, the Polish anthropologist and second cameraman, Waldemar Czechowski, the Tibetan Padma Wangyal, the American tibetologist Cyrus Rembert Stearns and myself as artist, film maker, initiator and leader of the expedition.

The route of the expedition, as far as the results given here are concerned, was as follows. Starting in lndia at Dharamsala we travelled around Spiti to Tabo, Kye, Lhalun, Kibber and the Pin-valley (names in international transcription), then to Kathmandu and Bodhath in Nepal, then into Tibet to 'Brikhung, bSam-yas, rTse-thang, Zwha-lu, rGyal-rtse, gZhis-ka-tse, sNye-thang, Bras-spungs, Lha-rtse, rNam-ring, Ribo-che and Ding-ri. In this brief report comments are offered on only five of the works of Thang-stong rGyal-po that we encountered: 1. the iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na; 2. the iron chain suspension bridge at Ri-bo-che, 3. the mchod-rten of gCung- resp. Pal Ri-bo-che as an example of architecture; 4. the frescoes of Ri-bo-che as an example of painting; and 5. the ritual pho-bar rdo-gcog as an example of the link between performance and theater.

We would not have discovered what we did, without the prelimary work of Stearns, his thesis on Thang-stong rGyal-po's life (1980) and his translation of the biography Lo-chen 'Gyur-med bde-chen (1609) under the title (1989)

The iron chain suspension bridge at Yu-na

The spelling Yu-na follows local pronunciation. The bridge is located in the upper sKyid-chu - valley north of LHa-sa south of 'Bri-khung til. The historic iron chains span about 30 meters, but contemporary steel cables stabilize the bridge today. The neighbouring former monastery of Yu-na was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Relics, such as carved wooden pillars, beams and stone reliefs, are embedded today in the foundations on both sides of the stream. Round boulders with central holes for the suspension of the chains with an iron bolt at either side seem to be original or are indistinquishable from traditional designs. On two of the iron links we found incisions.

The roughness of the inscriptions are probably more a sign of the difficult process of producing them during the red glowing phase of the hammering rather than a sign of age. Technically the inscription could only have been accomplished by use of a long chisel, which gave enough distance to protect the hands from the heat. The pointing of the chisel and the configuration oft he syllables must have been difficult. Therefore the characters are simple and read: rinchen lCzags-zam, Treasurable or Valuable lron Bridge. The often used term rin-chen denotes that the bridge must be made by, in honor of, or related to an important person, and/or must be situated at a holy place, etc.

The other incision we found supports this, saying: khyi-chu, dogwater, thus giving a date which could be the year 1442 within the Tibetan 60-year calendar cycle, if we consider the life time of Thang-stong rGyal-po relevant. Within his life the first dog-water-year would be the time, when he was only about twenty years old, the next one is the assumed date and the last one some time after his death. Both inscriptions give us reason to trust in the date 1442, since Thang-stong rGyal-po did not start bridge-building until he was 69 years old. Not surprisingly his biography mentions his activity in this area of the upper sKyid-chu right during that time.

The iron chain suspension bridge Ri-bo-che

Ri-bo-che monastery, called gCung-or Pal Ri-bo-che, not to be mixed up with Ri-bo-che in do-Khams, was, in addition to Chu-bo-ri, Thang-stong rGyal-po's main seat. Here several thousands of monks lived and Thang-stong rGyal-po's followers stayed until its destruction. The site at the 90 degree bend of the gTsang-po river, south of rNam-ring in U-Tsang, is dominated (and this is the only architectural structure which survived the ideological ‘purification' in tact) by a gorgeous seven-storey-high bKra-shis sgo-mang-type mchod-rten or sku-bum with a professional path skor-lam at the base, completing the mandala structure, and an iron-chain-bridge nearby.

The bridge is a childhood dream of a bridge. lt bridges the river gTsang-po, here in the upper part not wider than 100 meters, in two steps, a longer and shorter suspending part, as usual with Thang-stong rGyal-po's bridges, starting on a pile of river stones, originally found there or piled up, as Thangstong rGyal-po did at rTse-thang and other places, mentioned in his biography. Yakhide and leatherstrings, which are fastened to the links of the chain at either side, hang down and loop under wooden planks and logs, which function as foot paths. The chains serve as handrails as well, though they reach the height of one's hips. According to the biography the bridge was built in 1436; and as we anticipated, it looks its 550 years. The foundations of the bridge at the river side are crowned by ma-ni chu-skor and enormous trunks of old willow trees are used within the stone masonry work. The iron links themselves are the expected and known type that I have examined in Bhutan. They are one foot long, oblong shaped, more like squeezed ellipses, covered by a bronze-like smooth brownish to reddish patina, with a particular diagonal solding seam of arsenic-containing iron. Therefore the seams, usually the weakest part, are of additional strength and free of any rust, as the chains are entirely free of iron-mould, probably as a result of the rather unclean composition of the blacksmithed iron.

The perfect condition of the bridge which is an object of private daily worship and religious service by the inhabitants of the village finds its explanation, no doubt, in one of the prophecies known in the region: Buddhism will flourish in Tibet as long as this holy bridge stays. Thus the bridge has been defended and taken care of down through the centuries.

The documentation we took are the first photographs, films and videotapes ever. There is no other visual record of the bridge, apart from a sketch made by Peter Aufschnaiter more than forty years ago, passing by the village on his escape, not daring to enter it. The bridge can be seen at the very left of his drawing next to the stupa of Ri-bo-che.

The mchod-rten of Ri-bo-che

The mchod-rten is definitely of Thang-stong rGyal-po's hand, the construction process is described in detail in the biography. lt is a seven storey high hierarchical structure, if we count the structurally visual elements from the outside. Seen from the interior, we may add another storey inside the double-storeyed bum-pa and a three-dimensional mandala like the three sku-bum of rGyal-rtse, rGyang (this one Thang-stong rGyal-po is said to have helped building), and Jo-nang. The building was erected between 1449 and 1456 with the active support of the rNam-ring ruler who provided labourers and materials. There was also severe resistance by the workers, several assassination attempts, thefts and some collapses of walls. Wonderful stories concerning building techniques, spiritual teachings connected with the labour, and legends of the wild and crazy life of the Mahisiddha are told. After the mchod-rten's completion even the Emperor of China sent loads of presents to its consecration.

In this context it should not be neglected to mention the most important and most innovational architecture of Thang-stong rGyal-po in Bhutan, the lZlum-brtsegs lHa-khang in the sPagro-valley, showing some of the same inside features as the Ri-bo-che sku-bum. To the best of my knowledge, the construction of a mchod-rten as a temple did not occur before the time of Thang-stong rGyal-po.

The frescoes of Ri-bo-che

Within the very small and narrow chapels of the two storeys above the basement, used for professional circumambulation we observed and documented frescoes, luckily preserved in their lower parts. The rubble that fell from the massive wood, mud and slate rooves, when they had been destroyed by the Red Guards, protected the murals from decay. The frescoes are of great interest and, we believe, of Thang-stong rGyal-po's own hand, or commissioned by him. They were probably at least, in part, iconographically initiated and supervised by him. All the paintings of the second storey, for example, are mandala-compostions, a rarity in Tibet, and a significant attribute of centres for higher level-tantric practices.

The style of the paintings varies between floral design in earthy colors and free-flowing, heavily dark outlined figures of the same colour in material and character. Some of them have a transparent coating and the colours look different in brightness because of the slight gloss. We did not have enough time to examine them in the three days of our visit, which were filled with documentation work. They have to be urgently researched before they vanish under new frescoes, for 'restoration' work has already started. I may say here, that we believe from our experience as artists and researchers that the frescoes may date from as early as the 15th century. The artist's or artists' 'hand' is very personal, even quite daring within the given framework of the iconographic regulations. lt is a way of unpretentious, direct depiction of the necessary features of the figures, which proves the strong personality(ies) of the artist(s), characteristics which can be attributed to Thang-stong rGyal-po himself. Incomparable to other 'schools', we may only say, there is a certain relationship to Ngor-Evam, as far as the mandala-character is concerned.

The ritual Pho-bar rdo-gcog

We found the Thang-stong rGyal-po attributed ritual 'breaking of the stone' (pho-bar rdo-gcog) in the lonely and politically forbidden Indian border-valley Pin of Spiti in Himachal Pradesh. This ritual, which was believed lost forever after having been first observed by tibetologists over fifty years ago, was recorded in full with 16 mm film, video, photography and audio equipment. We agree with Stein that this bon-related ritual is a link between the story-telling and lecturing activities of the wandering ma-ni-pa, which I observed in Bhutan, and the Tibetan performances of A-Iche-IHa-mo. With actors of Ri-bo-che, Thang-stong rGyal-po founded a school of such fame, that according to witnesses they usually enacted the first drama among the various troupes at the Nor-bu gling-kha-'yoghurt'-festivals.

The abbreviated historical background of the three hour-long ritual can be given as follows. By request of Tsong-kha-pa, so the story goes, Thang-stong rGyal-po is asked to come to lHa-sa to help cure a severe epidemic. He arrives, miraculously flying on a white eagle, and finds the cause of the disaster to be either the demon dBang-rgyal, or Hala rTa-brgyad or Drang-srong chen-po gzha-bDud (Rahula with the sea-snake chu-srin) inside a stone at the threshold of the Jo-khang door. He initiates and then performs the ceremony on the market-place. The stages of the ritual are: asking the demon to leave the stone, then making an offering to him, then blaming him and urging him to go and finally demonstrating one's superior supernatural powers to the evil force by balancing his body on the tips of swords. Thang-stong rGyal-po is not able to have the demon react at all. So he announces he will break the boulder and force the demon to appear in open light. The threats have no effect so Thang-stong rGyal-po must do what he threatens. The rock, which requires two men to lift, is placed on the chest of third actor, lying in trance on his back on the floor. If the stone breaks by the first stroke of another riverstone, the omen is dharmakaya, by the second, nirmanakaya, etc.

The tone of the ritual is somewhat interrupted in the introductory scenes by a historical 'lecture' that begins humorously and ends with a deadly fight. The lecture sheds light on the unexplained relation between the 'King of the North' byang mi-rgod rGyal-po and the dharmaraja Chos-rGyal Norbzang, a story which could stem from the legend of Thang-stong rGyal-po building a mchod-rten at the northern border to prevent Mongolian infiltration. Surprisingly we found a Norbzang theme depicted in the nearby Tabo monaster on the tsug IHa-Khang-wall. But this, and its possible relation to the ritual, still has to be examined closely.

Before the ritual takes place a travelling altar mchod-bcams with, in this case, two Thang-stong rGyal-po statues, is set up and A-Iche IHa-mo-performances, the initial prayer is sung to Thang-stong rGyal-po, asking him to purify the site, space and situation.

When we showed our bu-chen-people from Sagnam the text Roerich had written down about 60 years ago with the help of the lo-tsa-ba chen-po, the lo-chen leader and main magician of the troupe of married lamas, they could hardly hold back their tears. This was their grandfather's and great grandfather's text, used over the generations and even now given further for the initiation of the leader's eldest son. This we take as a proof of having found the same lineage of pho-bar rdo-gcog-performers. Neither in Bhutan nor in Tibet could I find them or other bu-chen.

Our knowledge of the other diverse professional activities of Thang-stong rGyal-po and of his life story, which for reasons of space cannot be illustrated here, enable us now to give an exact picture of his works and life. A privately financed archive has been established in Berlin in order to collect and diffuse information on this Tibetan genius. We took some eighty hours of video documentation, three hours of 16 mm film and three thousand slides in the course of the expedition, but we are still looking for more photos, audio- and videotapes, films, literary sources and quotes, ritual and profane objects connected with his tantric practices, etc. An illustrated book and videofilm portrait is in preparation; and a film in eight parts has been planned. The first part, entitled 'The Demon in the Rock' and depicting the search for and discovery of the 'breaking of the stone' ritual, has already been cut.

Please help us trace additional materials by sending your information to: Thang-stong rGyal-po Archiv Berlin, Prof. Wolf Kahlen, Ehrenbergstraße 11, 1000 Berlin 33, Germany (Tel 030-831 37 08).

References

Aris, Michael 1979. Bhutan - The Early History of a Himalayan Kingdom. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Epprecht, Willfried 1979. Schweisseisen-KettenbrŸcke aus dem 14. Jahrhundert in Bhutan (Himalaya) mit arsenreicher Feuerschweissung. In Arch. EisenhŸttenwesen 50, Nr. 11, 473-477. Zürich: ETH ZŸrich, Mitteilung aus dem Institut fur Metallforschung.

Gyatso, Janet 1981. A Literary Transmission of the Traditions of Thang-stong rGyal-po: A Study of Visionary Buddhism in Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

'Gyur-med bde-chen. 1609. dPla grub-pa'i dbang-phyug brtson-'grus bzang-po’i rnam-par thar pa kun-gsal nor-bu’i me-Iong. Kandro: Tibetan Kampa lndustrial Society. P.O.Bir, Distr. Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, lndia, 1976.

Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark 1962. The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone. Folk, 4, 65-70.

Roerich, Georges N. 1932. The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone. Journal of Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, 2, 4, 25-51.

Stearns, Cyrus Rembert. 1980. The Life and Teachings of the Tibetan Saint Thang-stong rGyal-po, 'King of the Empty Plain'. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

------ 1989. King of the Empty Plain. The Life of the Tibetan Mahasiddha Tangtong Gyalpo. Unpublished translation of 'Gyur-med bde-chen.

Stein, R. A. 1956. L'EpopŽe tibŽtaine de Gesar dans sa version lamaique de Ling. Paris.

------ 1959. Recherches sur l’ŽpopŽe et le barde au Tibet. Paris.

© Thang-stong-Gyal-po Archiv Berlin